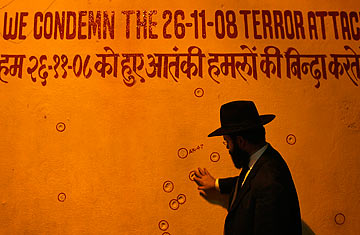

A rabbi touches a wall riddled with bullet holes in front of a Jewish religious headquarters in Mumbai after a multi-faith candlelight vigil for the victims of last year's attack.

The trial of Sabahuddin Ahmed for his work in facilitating last year's Mumbai massacre reveals an uncomfortable truth about India. Unlike his fellow accused, the Pakistani gunman Mohammad Amir Ajmal Qasab, Sabahuddin is Indian and for five years he was an alleged one-man sleeper cell hiding in plain sight. Even though he was arrested almost 10 months before the Mumbai attack, Sabahuddin had allegedly managed to provide enough information in terms of directions and diagrams to allow the terrorists to launch their assault with "absolute precision."

Ahmed easily exploited the gaping holes in the fabric of India's public safety — flaws that still exist a year after the attacks. According to his statement to police, Ahmed paid an acquaintance Rs. 50,000 (about $1,000) to buy admission to a college in Bangalore, and used his student ID to allay police suspicions while he was crossing from Kashmir to Bangalore — even as he was bringing a cache of weapons in by train. When he ran out of money, his handlers arranged to have funds sent to him through India's unregulated network of cash-transfer, or hawala, traders. For the equivalent of $2, an Indian, who had bought the right to smuggle jackfruit across the Bangladesh border, arranged for him to cross without documents to that country's capital Dhaka, where he met with agents of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the group believed to have planned the Mumbai attacks.

In the year since the Mumbai attacks, the Indian government has taken several steps to tighten security. It has improved co-ordination between the state and central intelligence agencies, devoted more men and equipment to security services and put intense diplomatic pressure on Pakistan to crack down on LeT and other jihadist groups. But there has been little discussion of how pervasive, low-level corruption can compromise national security. The various brokers and middlemen who helped Sabahuddin never knew he was involved with a jihadist group; he appeared to be simply another young man living in the gray margins of Indian society, paying a little here and there to grease the wheels of an enormous but inefficient bureaucracy and police force. Until those margins are narrowed, security experts say, India continues to be the world's biggest soft target. "We remain as vulnerable today as we were on 26/11," says Ajai Sahni, Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management, using the shorthand for the Nov. 26, 2008, attacks. "Corruption undermines and negates everything."

In India, corruption is taken as an unfortunate fact of life even for otherwise law-abiding citizens. For example, ration cards are a lifeline for India's poor, giving them access to subsidized rice, lentils and kerosene. But to get them, you need a birth certificate or proof of residence —something many Indians lack. So, they often pay clerks to issue ration cards without a supporting document. A tea-shop worker in Mumbai told me he bought one for Rs. 5,000 ($111). Meanwhile, the ration card is a step toward a passport. In theory, passports are difficult to get; police officers are supposed to visit you in person to verify your identity and address. However, according to an entrepreneur who helps set these things up, as long as you don't have an arrest record, the police will skip that formality —for a few hundred rupees. There is no need for counterfeit documents; for a fee, authentic ones are readily available.

Given the size of the Indian bureaucracy, with 18 million public employees serving more than a billion people, "you can never create a foolproof system," says Ajay Behera, an assistant professor at Jamia Millia Islamia who has written extensively about regional security. But in such a porous system, he says, a small group of relatively uneducated people can organize a major operation. "Almost anyone can do anything here," Behera says. "It doesn't require that high a level of sophistication."

Making India harder for would-be terrorists to penetrate would require reform not just of the bureaucracy but also the police. Local and international human-rights groups have exhaustively documented the crisis in Indian policing, criticizing the Indian police for everything from taking bribes to engaging in torture and extrajudicial killing. Eight national commissions have also recommended wide-ranging police reforms, few of which have been implemented.

Lower-level Indian police officers and border guards remain underpaid and undertrained, while being given almost unchallenged authority over the people they are meant to serve. A 26-year veteran of the Mumbai police told TIME that his monthly salary is Rs. 10,360 (about $230). Less than a week before the one-year anniversary of the Mumbai attacks, the Times of India reported that police officers assigned to round-the-clock duty guarding the Taj Mahal Palace and Towers Hotel had been provided with no quarters, so they were sleeping outside, under the Gateway of India monument.

In these circumstances, security experts say, those at the front lines of national security are prone to accept even small bribes. By late 2006, after the July 2006 Mumbai train blasts and an October 2006 attack in Kashmir, security on the Indian border had become very strict. But Sabahuddin, in his statement, says that Rs. 10,000 ($222) was enough to get past the Central Reserve Police Force. "They asked me to give my address and I gave them a fake address in Kolkata," he says. "To verify me, they called my friend... [and] they got confirmed that I am an Indian and allowed me to travel."

The Mumbai attackers are believed to have come by sea from Karachi, and over the past year, the Indian government has added new vessels to tighten up security along its long maritime border with Pakistan. But Behera estimates that getting through a checkpoint costs only about Rs. 5,000 ($111). Despite the necessary investment in new boats and training, corruption is still a vulnerability, says Pushpita Das, who is researching coastal security at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. "The liability still remains."

The responsibility for cleaning up the dark corners of Indian life lies not only with the police. Citizens, too, have to demand a better system. Behera says that Indians use elections to throw out politicians perceived as corrupt, but so far, "there is no great social movement against corruption." That could change. India's 2005 Right to Information Act has emboldened some of its citizens to question once-omniscient bureaucrats, but the progress of reform is slow. A judgment on the Mumbai attacks may be handed down in a matter of months; India's verdict on itself will take much longer.