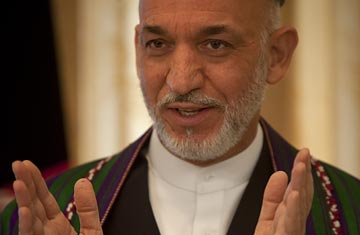

President Hamid Karzai speaks to the media at Kabul's presidential palace on Sept. 17

The acceptance by the U.S. and NATO of a second term of office for Afghanistan's President Hamid Karzai has raised concerns among many Afghans skeptical of the legitimacy of his re-election. That acceptance was announced in Washington and Brussels on Sept. 29, at least a week before Afghanistan's Electoral Complaints Commission releases its final verdict on a recount of thousands of potentially fraudulent votes that could either confirm Karzai's initial first-round victory or — if his tally falls below 50% — order a runoff vote against his closest challenger, Abdullah Abdullah. But while the Western powers may have jumped the gun with the announcement of support, it seems inevitable that Karzai will eventually emerge victorious even after a runoff.

The U.S., NATO and the U.N. — whose senior representative to Afghanistan, Norwegian Kai Eide, was accused by his American deputy, Peter Galbraith, of tacitly favoring a Karzai victory following the election debacle (Galbraith was fired this week) — will now be forced to work with an Afghan leader that has not only distanced himself from Western tutelage but also lacks legitimacy in the eyes of his people.

Relations between Karzai and his Western backers deteriorated significantly over the past couple of years, particularly after the onset of the Obama Administration. Instead of stinging Karzai into cleaning up his act, public criticism from Washington enabled him to set himself up as a leader at odds with the U.S., boosting his support in some sections of the population. He sought to strengthen his position through alliances with regional power brokers, including warlords accused of major human-rights abuses and known drug traffickers — people he will be beholden to as he enters a second term.

"These leaders, these warlords, we witnessed them as they destroyed our country over the past decades," says Sanjar Sohail, editor of the national Eight in the Morning newspaper. "Previously they destroyed with the power of the gun. Now they can destroy with the power of democracy."

Still, the U.S. and NATO have little choice but to work with the leader they have, even if he's not the leader they wish they had. Karzai believed that Washington was trying to get rid of him ahead of the election, and he'll see his victory as a triumph also over those in Western capitals who had sought his ouster. Having secured another term of office, and with the West desperate to save its mission in Afghanistan from collapse, Karzai has the upper hand — and that will make it all the more difficult to cajole him into fighting corruption and delivering the good governance that is key to the campaign against the Taliban.

Presidential spokesman Humayun Hamidzada acknowledges tension in the relationship between Karzai and the international community, especially the U.S., but contends that the most difficult times are over, especially now that Karzai has what he calls a "fresh, strong mandate." He continues, "We have always agreed on what should be the end result [for Afghanistan] but not always on how to get there. We are a very different government now than we were eight years ago, so we can be more partners than beneficiaries." Perhaps. But the reforms in governance and the fight against corruption that Western powers are demanding would involve tough choices for the incumbent, many of whose key supporters are part of the problem.

The international community has protested vocally against Karzai's affiliation with warlords such as his newly appointed vice presidential running mate, Marshal Fahim, and Abdul Rashid Dostum, a northern warlord whose flagrant disregard of Afghan law over the past several years was overlooked in exchange for his support in the election. Such protests have had little effect, says Ahmad Nader Nadery of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. "Rhetoric and public criticism that pushes a leader to a corner will not work, especially in Afghanistan where pride is an issue. If you just go in and say 'Don't deal with Dostum' or 'Stop corruption' and leave, no one will feel the pressure."

Even now, Nadery claims, Washington has more leverage than it knows. For example, many of the salaries of Karzai's coterie of close advisers are paid by the U.S. "If you have a clear demonstration that resources would be cut off from different operations in the [presidential] palace, that kind of pressure would have an impact," he suggests.

While many of the comparisons between the NATO mission in Afghanistan and the failed Soviet occupation in the 1980s are flawed, there is an unfortunate parallel in at least one respect: Moscow's insistence that Afghans recognize their puppet government, despite its failure to deliver to the people. "Everyone is focusing on the number of troops the U.S. has in Afghanistan," says analyst Haroun Mir, director of Afghanistan's Center for Research and Policy Studies. "The Russians had twice as many troops [as the NATO coalition does now] but they failed, not because they were weak, but because the Afghan government was never accepted by the people. If people do not accept and recognize the legitimacy of the Afghan government we cannot force them with foreign forces. And that is where we are going." Karzai has a lock on power in Kabul for the next five years, but if can't be persuaded or compelled to fundamentally reform his government, the echo of the Soviet example may grow louder and more ominous.