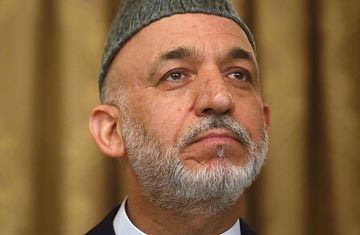

Afghan President Hamid Karzai listens during a news conference on election day in Kabul

Despite repeated claims of neutrality in the Afghan elections, the Obama Administration is deeply concerned that a Hamid Karzai victory would compound the challenges the U.S. faces in that country. Having made no secret of its dissatisfaction with Karzai's performance as President, the White House may now have to deal with an ally who feels slighted and scorned — and who has little incentive to go along with U.S. goals in Afghanistan.

Karzai's fall from Washington's grace has been spectacular. He was feted as an Afghan Mandela by the Bush Administration and enjoyed unparalleled access to the White House. Bush and Karzai routinely chatted in videoconferences. Obama, however, has treated the Afghan leader like spoiled fruit.

An early portent of the change came during the presidential campaign last year, when Joe Biden visited Karzai in Kabul. The two men got into a verbal duel over questions of corruption in the Afghan government; Biden stormed out in the middle of dinner. In a society where decorum is paramount, this was deeply humiliating for Karzai — especially since word quickly got to the press.

After Obama's Inauguration, things got worse. Officials in the new Administration made no secret of their contempt for Karzai, whom they viewed as spineless and inefficient, too tolerant of drug smugglers. Allegations that some members of his family were in the drug trade didn't help. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has described Karzai's administration as a "narco-state." And last week, another meeting with a visiting American — special envoy Richard Holbrooke — descended into angry words.

For all their protestations of neutrality, U.S. officials would be relieved if Karzai is defeated in the election: his closest rival, former Foreign Minister Abdullah Abdullah, would represent a fresh start. But it's looking increasingly likely that Karzai will squeak by to victory: on Wednesday, he had 47% of the votes counted and seemed on course to get the 50% he needs to prevent a runoff.

That sets the stage for tense relations between Washington and Kabul, a complication the Obama Administration doesn't need as it grapples with the Afghanistan problem. The most immediate flash point will come in a matter of days, when the election results are officially announced. Getting Abdullah to accept defeat will be hard: there have been widespread allegations of fraud. If the former Foreign Minister contests the results in the street — in the manner of Iran's Mir-Hossein Mousavi — that could set off an ethnic conflict between Karzai's Pashtun base and his rival's Tajik following (Abdullah's father is Pashtun, his mother Tajik). "The challenge is to ensure that the election doesn't end up dividing the country," says a U.S. official familiar with Afghan policy.

If Abdullah does go quietly, the Obama Administration will need to get Karzai to clean up his act. "We need to turn the clock back — take Karzai back to where he was in 2003-'04," says the U.S. official. That was before the Afghan leader had made questionable deals with warlords and tribal chieftains and looked the other way as drug smugglers grew ever more powerful.

Karzai, however, may be in no mood to go back. If he wins the election, it will be in no small part because those very warlords and chieftains delivered big blocks of votes. If anything, he will be even more indebted to them. And he is unlikely to have forgotten his repeated humiliation by U.S. officials. That's not to say Karzai will be outright hostile to the U.S. He needs American troops and aid. "What other recourse does he have — he has no other allies," says Ashley Tellis, a South Asia expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "If the U.S. checks out, Karzai doesn't survive."

But Afghanistan experts worry that Karzai will be passive-aggressive: not openly opposing the U.S. but deliberately dragging his heels when it comes to cleaning up corruption and reforming his administration. U.S. officials say rampant corruption has contributed to the resurgence of the Taliban in the past two years. "If Karzai continues down the same path, it will be hard to fight the insurgency," says Tellis.

The solution favored by the White House is to pressure Karzai into installing a powerful second in command: a Prime Minister who would run the government's day-to-day functions. Abdullah himself is a possible candidate, as is another presidential contender, former World Bank official Ashraf Ghani, who is Pashtun. Both men have clean reputations and some administrative experience, although it is far from clear that they have the political skills to navigate Afghanistan's multiethnic society.

In any case, will Karzai be amenable to such a deal? "He understands that continued support from the West is contingent on some accommodation," says Jason Campbell, an Afghanistan expert at the Brookings Institution. "He can see some benefit in having someone like Ghani — it helps with his credibility in the West."

But first Karzai will need to be mollified that he is no longer in the doghouse with Obama. Perhaps the White House could send Biden to kiss and make up?