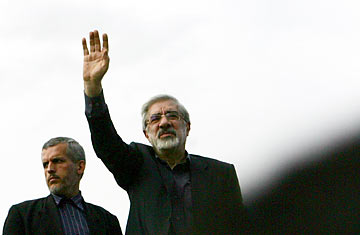

Reformist candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi speaks to supporters as they gather on the streets of Tehran to demonstrate against the results of the Iranian presidential election on June 18, 2009

Iranian presidential candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi lashed out defiantly at the June 29 certification, following a partial recount initiated by the clerical body that oversees Iran's elections, of the June 12 re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. "From now on, we will have a government ... whose political legitimacy will not be accepted by the majority of people, including myself," Mousavi said in a statement.

Yet Mousavi's refusal to accept defeat in an election he believes was stolen remains largely symbolic; the reality is that the protest movement he has led to challenge the results is running out of options. The authorities have taken control of the streets of Tehran through an overwhelming deployment of force that has prevented even the smallest of opposition gatherings from taking place. They have arrested scores of opposition candidates and journalists and forced most of the Western press to leave the country. And while the government has put state media at its disposal, spinning the opposition protests as the work of foreign governments, Mousavi is reduced to speaking through statements posted on his website.

With the opposition denied the public space to continue its campaign except through relatively muted and scattered protest actions, the center of gravity of the challenge to Ahmadinejad's camp will likely move behind closed doors. Mousavi implied as much in his statement, saying he will join a group that will push for reforms through legal means. Among the proposed changes he cited were an overhaul of election laws to prevent future instances of vote-rigging, an end to surveillance and control of electronic communications, freedom of the press and the release of reform politicians and journalists. Mousavi's statement comes on the back of several other statements from influential opposition politicians and clerics that called for protesters to cede the streets to the security forces but to carry on the struggle as a loyal opposition. "We reserve the right to protest against the result of the election but believe that people should not pay any higher price," said the reformist Combatant Clerics' Assembly, "and that escalating tensions and street protests are not the solution."

But it's not clear that the authorities will allow the protest movement to morph into a legal political movement. Until now, power in Iran (unlike in most Middle Eastern countries) has been dispersed across a number of institutions and bodies, from clerical councils to elected bodies such as parliament and the presidency, and the system was designed to allow for competition among different political groupings within the bounds of loyalty to the Islamic system. But the election and its aftermath highlighted the extent to which power has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of just a few politicians and their backers in the security services.

Many of the politicians and clerics who supported Mousavi are now in jail, despite having been known as pillars of the state and veterans of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Others have found themselves politically neutered. In the days after the election, many analysts speculated that the powerful former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was using his chairmanship of the Assembly of Experts — the body that chooses and oversees the clerical Supreme Leader of Iran — to mount a challenge to the tenure of Ayatullah Ali Khamenei. So far, that challenge has not materialized.

As the influence of stalwart political and clerical figures recedes, the power of the leadership of the security services appears to be growing. On Tuesday the head of Iran's armed forces demanded that the European Union apologize for its alleged role in fomenting postelection protests as a precondition for Iran's resuming negotiations over its nuclear program. Such forays into international diplomacy have not traditionally been the prerogative of Iran's military.

Anyone looking to reintegrate opposition leaders into the political system may struggle to persuade the ascendant hard-line faction, which has painted the protest movement as the work of foreign powers bent on undermining the Islamic Republic. Indeed, the chief of the Basij militia — the paramilitary group behind much of the crackdown against protesters — asked Iran's chief prosecutor to investigate Mousavi for his role in the protests on the grounds that they undermined national security. The charge carries a maximum of 10 years in prison. But there will be significant pressure from other loyal sections of the regime to accommodate some of the concerns of those aggrieved by the election. The extent to which these concerns are addressed may be a measure of the relative strength of the hard-line security establishment within the regime.