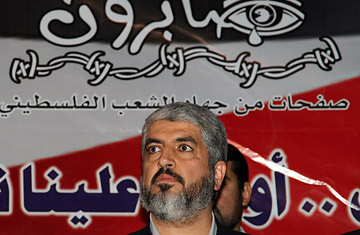

Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal

Israel's new government is a headache the Obama Administration doesn't need. Compared with Tzipi Livni, the woman he narrowly beat out, and even Ehud Olmert, the man he succeeds, incoming Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahuis cool toward a Palestinian state. And although it includes the moderate Labor Party, Netanyahu's ruling coalition teems with right-wing figures like Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, whose call for a loyalty oath directed at Israel's Arab citizens dismays even Israel's staunchest friends.

But if Israel's new government is making the Obama team anxious, it's nothing compared with the government that could be coming together next door in the Palestinian territories — where President Mahmoud Abbas and his Fatah party may join hands with the Islamist militants of Hamas. That's a problem, since the U.S. won't have anything to do with Hamas or any government in which it takes part. A few months ago, when Hamas was at odds with Abbas and at war with Israel, that was an easy position to take. But now it's becoming harder. And sooner or later, the U.S. may have to come to the same painful realization it has arrived at in Iraq and Afghanistan: the only thing worse than talking to terrorists is not talking to them. (Read "Rift Between Hamas and Fatah Grows After Gaza.")

In a way, Hamas is the final frontier. After 9/11, the Bush Administration vowed it would not negotiate with terrorists — not just al-Qaeda but national terrorist movements and the regimes that sponsored them. More than seven years later, that hard line has melted. The Bush Administration negotiated with North Korea despite listing it as a state sponsor of terrorism. In Iraq, it not only talked to Baathists who had been killing other Iraqis and our troops, it paid and armed them. And the Obama Administration has gone further. It has advertised its willingness to negotiate with the governments in Damascus and Tehran, both terrorism sponsors, according to the State Department. It is also mulling overtures to the Taliban, which is killing U.S. troops and ordinary Afghans nearly every day. The U.S. still doesn't talk to Hizballah, but we do talk to the Lebanese government, in which Hizballah plays a — prominent role. (See pictures of 60 years of Israel.)

We've softened our stance for two basic reasons. First, our policy of shooting and stonewalling wasn't succeeding in either eradicating terrorist movements and their patrons or moderating them. Second, U.S. policymakers decided that movements like the Baathists and the Taliban and regimes like those in Syria, Iran and North Korea are fundamentally different from al-Qaeda. They are different because their goals are national or regional, not global. The Baathists want to run Iraq again; the Taliban wants to reclaim power in Afghanistan; the Iranians want to perpetuate their dictatorship and wield influence across the Middle East. Those goals may be unacceptable, but we've decided that they bear enough relationship to reality to be worth talking about.

The argument for talking to a government that includes Hamas is that Hamas is more like the Taliban and the Baathists than like al-Qaeda. First, Hamas is deeply rooted in Palestinian society and thus very difficult to uproot by force. It operates a vast social-welfare network and according to many polls is now the most popular Palestinian political party. For 22 days beginning last December, Israel pummeled its institutions in Gaza, but the war hasn't turned Palestinians against the group. To the contrary, it is more entrenched than ever in Gaza and on the verge of seizing power in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon as well. (Read "Fatah and Hamas: Heading for a Showdown in Lebanon.")

So far, the U.S. and Israel's strategy has been to keep Hamas-ruled Gaza poor while improving life in the West Bank, which is governed by Fatah and Abbas, in the hope that Palestinians — seeing the contrast — will desert Hamas, thus forcing it to capitulate to our demands. But the strategy has failed for three big reasons. One is Fatah, which is still widely considered incompetent and corrupt. Another is Israel, which hasn't given Abbas what politically he most needs: a halt to — or reversal of — West Bank settlement growth. The final reason is Hamas itself, which has an incentive to foil our plans. All the organization has to do is what it did late last year: lob enough missiles into southern Israel to provoke an Israeli response. When that happens, the sight of Abbas standing idly by while Palestinians die pretty much wrecks his credibility. (See pictures of life under Hamas in Gaza.)

So there's a negative reason for the U.S. and Israel to talk to a government that includes Hamas, the same negative reason the U.S. talked to the Baathists and seems set to talk to the Taliban: not talking isn't working out very well. But that alone doesn't justify a change in policy. Critics point out that dealing with Hamas would break precedent, since the U.S. never publicly dealt with Yasser Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization until it accepted Israel and renounced violence. They say Hamas must be forced to choose between the ballot and the bullet. They're right — it must. But what matters is getting it to choose, not whether Hamas chooses before we talk to it or after. The Irish Republican Army only publicly renounced armed struggle in 2005, a full seven years after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought its civilian wing into the political process. And even in the case of the PLO, the U.S. and Israel negotiated secretly with Arafat for years before he finally met our demands.