Southern African leaders failed to end Zimbabwe's political crisis amid threats by President Mugabe to form a government excluding his rival.

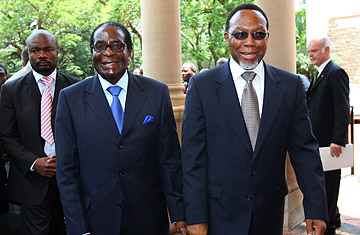

Power sharing negotiations between Robert Mugabe's regime and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) ended in confusion Tuesday, when mediators announced a deal — only for the opposition to immediately deny one. "All the parties expressed confidence in the process and committed to implementing the agreement," South African President Kgalema Motlanthe told a press briefing in the South African capital Pretoria after the 14-hour meeting — the latest in a series of regional summits on the issue. An accompanying communiqué said agreement had been reached on key points, including the naming of MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai to a newly created post of Prime Minister on February 11, and the shared control of the Home Affairs ministry, which controls the police, for six months.

Within minutes of Motlanthe's announcement, though, the MDC released a statement saying the deal fell "far short of our expectations" of a "just resolution." While not rejecting the deal outright, the opposition party said that its national executive council would meet on Friday to finalize its response.

It has been almost 10 months since Zimbabwe's opposition beat Robert Mugabe's ruling Zimbabwean African National-Popular Front (Zanu-PF) in a general election. Mugabe refused to accept the outcome, calling it a "mistake," and unleashed a wave of violence against MDC supporters. After winning a run-off against Tsvangirai — the MDC leader had withdrawn in the face of the violence — Mugabe unexpectedly announced his intention to share power. Ever since, the two sides have been deadlocked in negotiations over how that might be accomplished. In the meantime, Zimbabwe's humanitarian crisis has sharply deteriorated. Inflation has spiraled out of control, unemployment is near universal, poverty is endemic, hundreds of thousands of refugees have fled the country and close to 3,000 people have died of cholera since the collapse of water and sewage systems in the capital, Harare. (See pictures of political tension in Zimbabwe.)

A resolution to the crisis in Zimbabwe would resonate across Africa for a number of reasons. First, Mugabe is one of the last, and certainly the most prominent, old-style African despots, liberation heroes who quickly turned on their own people once in power and presided over catastrophic corruption, incompetence and human rights abuses. His departure, even a mere dilution of his power, would herald the end of an unhappy chapter in Africa's modern history. Second, the success or failure of South Africa in resolving the crisis is seen as a crucial test of Africa's ability to manage its own affairs. Third, ending the political dispute in Zimbabwe is also the necessary starting point for pulling Zimbabwe out of humanitarian disaster. If credible power-sharing was achieved, the West would lift sanctions against the regime and resume aid, aid agencies, who have faced repeated disruption to their work could get on with the job of saving lives and, once law and order improved, trade and business would also pick up. Conversely, failure to resolve Zimbabwe's crisis would have negative implications, intensifying the suffering in Zimbabwe, spurring more to flee into neighboring countries and signaling to other dictators that their rule will be tolerated by their fellow Africans.

On Tuesday, most Zimbabweans were gloomy about the prospects of a resolution. University of Zimbabwe lecturer and political commentator John Makumbe said Tsvangirai had been pressured to accept a "half-baked agreement" before discussing it with his party. He added that he thought the U.S., Britain and Europe would also reject the deal. "Our woes will continue," he said. "The country will continue to be in limbo." In central Harare, newspaper vendor Kingstone Bere accused South Africa and other mediators of siding with Mugabe, adding they were "not concerned about the welfare of Zimbabweans, but about the welfare of Mugabe."

By contrast, a Zanu-PF politburo member was delighted by the outcome. "[This] will take the country forward," he said. "It is the best way for Zimbabwe." As for what that way forward might be, deputy information minister Bright Matonga told the BBC: "There is not going to be any negotiations. I think that process is done, concluded ... and the President will form a new cabinet."

— With reporting by Correspondents inside Zimbabwe