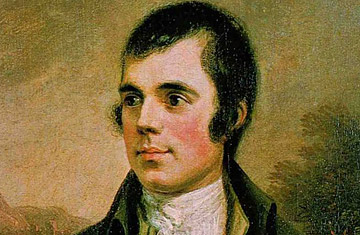

Robert Burns

Oh, the Scots. They have their kilts and their bagpipes and their knotted, lyrical accents that make them sound as if they're perpetually chewing something. And best of all, they still get excited about an 18th century poet. Every year on Jan. 25, people gather at dinner parties all across Scotland to celebrate the life and works of their country's most famous poet, Robert Burns — and they do so by singing to the food. (See pictures of the world's wackiest holidays.)

Robert Burns was born 250 years ago, on January 25, 1759, in Alloway, Scotland. His father was a tenant farmer and his mother never learned to write, but Burns read voraciously and managed to secure a fairly thorough education. His family had very little money — when his father died, he left the family bankrupt — which inspired the egalitarian, anti-authority themes that would appear in Burns' future works.

At 15, he began to work his father's fields alongside a young girl named Nelly. He soon found himself filed with passion for what he would later call "man's first great pleasure in life," and wrote one of his earliest poems about the girl. As Burns grew, so did his success with women. Male friends became his unwilling wingmen and complained that Burns would leave them at a tavern if a feminine opportunity presented itself. Over the course of his life, the poet would father fourteen children by six different mothers (only one of whom he married).

Burns wrote in Scots, a dialect that looks familiar but confusing to modern English speakers (he penned "Auld Lang Syne," which most of us can pronounce but not interpret). In 1786, he published his first book of poems, on everything from religious hypocrisy to a typical Scottish Saturday night. The poems were catchy, sarcastic and light; the book was an instant success. Like a struggling actor who lands a part on a major sitcom, the fame came hard and fast — everybody in Scotland suddenly knew who he was.

1786 was a tumultuous time for Burns; in addition to his newfound success, it was also the year that his lover, Mary Campell — for whom he penned his famous "Highland Mary" — died while giving birth to his child. Not that he had much time to mourn; the previous year, he impregnated his family's servant girl and brought shame to her family by not marrying her. He then took up with a young woman named Jean Armour, but she became pregnant too. Burns tried to marry Armour, but her father wouldn't have it. Then the poems were published, Burns became famous, and what do you know, suddenly the marriage offer seemed more appealing. In 1788, after a few other flings with a few other women, the two eventually wed.

It's hard to raise a family on a poet's salary, of course, so Burns took a job as a tax inspector while still writing — and farming — on the side. He switched from poems to songs, and produced a number of tunes still famous today: "A Man's a Man for A' That," "A Red, Red Rose," and of course the New Year's Eve jingle about old acquaintances. Unfortunately, Burns had a weak heart, and strenuous requirements of a farmer's life took their toll. He died in 1796 — on the very day that his wife gave birth to his last child. Poets are dramatic like that.

Scotland went into mourning mode; ten thousand people attended his funeral and he was later named national poet of Scotland. The Scots refer to him as "The Bard," others as "The Scottish Bard," to distinguish his nickname from Shakespeare's. And of course, there's Burns Night.

In 1801, some of Burns' friends and admirers decided to honor the departed poet with a dinner. They did it again the next year, and the next; by the early 19th century, Burns Clubs all over the country were hosing annual Burns Suppers. The celebrations were only for men — despite the poet's fondness for the ladies — and the menu has never changed.

Burns Night procedure is highly structured. After the guests arrive and take their seats at the table, the chairman (what? don't your dinner parties have a chairman?) asks them to stand and receive the haggis. Everyone rises as the entrée of entrails — haggis is made by stuffing a sheep's heart, liver and lungs along with oatmeal and spices into the stomach lining, so that it looks like an oddly distended football — arrives on a platter, usually with a bagpipe band following behind. Someone then gives a boisterous rendition of one of Burns' poems, "Address to a Haggis." When he recites the line about cutting the food ("An cut you up wi ready slight") he stabs the haggis dramatically, holds the food aloft and concludes with the line, "Give her a haggis!" Then everyone toasts the haggis, which is subsequently served and eaten with side dishes of neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes). Men give a sarcastic, sexist toast "to the lassies" and the women (most dinners now allow women) reply with a sarcastic toast about how much they hate men. More poems are recited, songs are sung, and everyone drinks a lot of whisky.

In recent decades, Burns Night celebrations have extended into a sort of weeklong series of parties, some only loosely affiliated with the poet. There are restaurant specials, barroom activities — anything that allows for a rowdy party and maybe a bite of haggis. Today's television-and-videogame world rarely has time for poems, but then again, the skirt-chasing, whisky-swilling Robert Burns wasn't your typical poet.