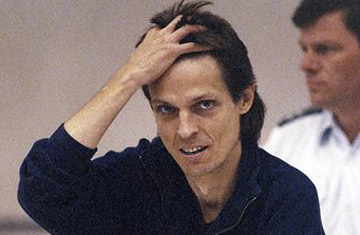

Christian Klar

For all its terrorist bravado, the story of the Red Army Faction (a.k.a. the Baader-Meinhof gang) ended with a whimper. On November 16 1982, German policemen hiding in the soil and foliage of a cold, wet forest near Hamburg, spotted a skinny man in a tracksuit moving erratically toward them. "Don't shoot!" the man shouted as the policemen armed with machine guns jumped out of their hiding places to arrest the completely exhausted Christian Klar, the last member of the so-called "second generation" of the R.A.F. still on the loose. But if Klar's arrest and conviction was meant to close one of the most traumatic chapters of postwar German history, his imminent release has forced the country to revisit the R.A.F.'s legacy of leftist terror.

A German court ruled Monday that Klar, serving a life sentence for his involvement in the murder of nine people, among them former Dresdner Bank chief Juergen Ponto, attorney general Siegfried Buback and industrialist Hanns-Martin Schleyer, as well as in 11 attempted murders, will be released on parole at the beginning of next year after 26 years in prison.

The verdict brought a storm of protest e-mails and phone calls to the court. Politicians and relatives of the victims expressed outrage, and Juergen Vietor, co-pilot of a Lufthansa plane hijacked by the R.A.F. in 1977, sent a protest letter to president Horst Koehler and returned the Federal Cross of Merit he had been awarded by the state. "Why", Vietor's letter says, "do perpetrators receive more care and attention in our state, than victims?"

Critics of the court's decision note that Christian Klar has never apologized for his deeds, and to this day refuses to divulge the identity of the mysterious man on a motorbike who fired the shots that killed Siegfried Buback. Klar had also made public statements from prison expressing anti-capitalist beliefs, which some claim are proof of his continued ideological zeal.

The court defended its ruling in a statement citing expert testimony to the effect that Klar no longer represents any danger to society. Justice Minister Brigitte Zypris called the verdict "an act entirely in accordance with the rule of law."

In 2003, Klar had filed a clemency plea with then-president Johannes Rau, who declined to made a decision. His successor, Horst Koehler, after a heated public debate, finally rejected Klar's appeal in May last year. Klar's accomplice, Brigitte Mohnhaupt, had earlier been released on parole after serving a 24 year sentence.

The discussion shows that Germany still struggles with the events that took place in the autumn of 1977, the "Deutscher Herbst" (German Autumn) when the second generation of the left-wing terrorist group R.A.F., composed mostly of young, well-educated, middle-class Germans, brought the country to the verge of a state of emergency. The main aim of the campaign of violence by the "second generation" was to free the imprisoned leaders of the group's founding generation — Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof and others — who regarded themselves as part of a global fight against imperialism and capitalism. The R.A.F. was born out of the non-violent left-wing student movement of the 1960s, which became steadily radicalized in response the Vietnam war and repression of student protest. Having turned to violence, the smaller conspiratorial group carried out several bank robberies as well as bomb attacks on U.S. military facilities in Germany and on German security institutions, in the course of which four people were killed and 41 injured. Many young Germans at the time, among them former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, who in 2000 was even questioned as witness in a trial over a 1975 attack on the Opec conference in Vienna, had been initially sympathetic to the goals of R.A.F., but were later disillusioned by the group's excessive use of violence.

"People had the experience that the state was powerless; it was an feeling of complete helplessness," says Butz Peters, a lawyer and author of several books on the R.A.F. about its reign of terror. "For those who were around at the time, many things are now cropping up again," he says, of the emotional reactions to the Klar ruling.

The court decision on Klar's release stoked a debate that flares up periodically in Germany. Last year, the issue was the release of Klar's colleague, Mohnhaupt. Another R.A.F. member, Eva Haule, who studied photography in prison and even had her work there exhibited, was also released last year, and other members who had hidden in East Germany but were arrested after its collapse have also been released after serving relatively short sentences, and are living unobtrusively. But Germany's ongoing fascination with the R.A.F. episode of its history was underscored by the movie The Baader Meinhof Komplex, which was a box office success but was denounced by Ignes Ponto, widow of Juergen Ponto, as distorting history and glorifying violence.

After Klar's release there will be only one former R.A.F. member left in prison — Birgit Hogefeld, who is unlikely to be released before 2011. But Peters doesn't expect Germany to exorcise the ghosts of its homegrown terrorism anytime soon: "The German soul," he says, "definitely hasn't yet coped with the trauma of the R.A.F."