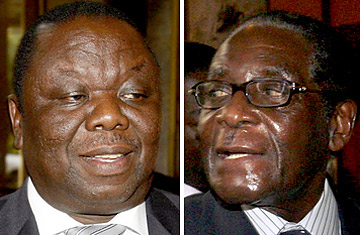

Zimbabwe opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, left, and Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe, right.

It was Groundhog Day in Zimbabwe on Monday, as yet another attempt to broker a power-sharing deal between President Robert Mugabe's Zanu-PF party and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) failed, despite the efforts of a mediation team from Zimbabwe's neighbors. Once again, the sides simply agreed to continue talking, this time at an "extraordinary summit" of the Southern African Development Community to be held in the next two weeks. The MDC repeated its accusation that Mugabe's regime showed a "serious lack of sincerity and good faith"; the ruling party responded that it would not countenance any deal that sought to overturn its achievements after 28 years in power.

Zimbabweans may have a hard time determining what those achievements might be when the official inflation rate is 231 million percent — although quite how that is calculated when there is no food in the stores is anybody's guess. Most of the economically active population is unemployed, and the long predicted humanitarian crisis has begun to bite, with 5 million people in need of food aid. Hospitals are reporting a rising number of deaths from malnutrition. And the Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights says cholera has killed 120 people since January. "Water supply is irregular or completely absent in most urban areas, burst sewage pipes continue to be left unattended and there is a lack of refuse collection," it warns. "These factors create ideal conditions for the outbreak and spread of diseases such as diarrhea, including its deadly forms of cholera and dysentery." In a statement Monday, U.N. secretary general Ban Ki-Moon said he was "deeply concerned that the population of Zimbabwe in both rural and urban areas faces many challenges, including critical shortages of all food, essential drugs, basic services, and clean water." On the streets of Harare, anger at the situation spilled over Monday when a crowd of hundreds marched on the talks venue waving placards proclaiming "Tafa Nenzara" (We are dying of hunger). The police beat back the protesters and arrested more than 50.

And still the politicians bicker. Former home affairs minister Dumiso Dabengwa, who served under Mugabe, criticised the endless negotiations at a time of crisis, and told TIME both sides should have agreed on the allocation of ministries when they fixed Mugabe's and Tsvangirai's positions. But the blame for the impasse lies chiefly with the regime. Mugabe's party lost its parliamentary majority in a general election on March 29, and Mugabe himself finished second in the presidential race behind MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai (although Tsvangirai failed to win an outright majority, forcing a runoff race). That prompted Mugabe's security forces to unleash three months of terror against opposition supporters across the country, during which almost 200 MDC activists and supporters were killed. The violence prompted Tsvangirai to pull out of the run-off, leaving Mugabe to win unopposed.

Although Mugabe immediately announced that he would accept power-sharing talks with the opposition, he has shown little inclination to accept any outcome that diluted his power. So, talks dragged on until Sept. 15, when the two sides agreed to keep Mugabe as President and appoint Tsvangirai as prime minister, ostensibly dividing authority between the two offices. But talks on establishing a working national unity government have floundered, as Mugabe refuses to cede control over any of the ministries that control the security apparatus, and other posts that have been essential to ensuring Zanu-PF rule. Instead, Mugabe has moved to appoint his own choices to each government department, negating the power-sharing principle.

The Southern African mediators who presided over the latest talks expressed concern over the disagreement over cabinet posts — particularly the interior ministry, which controls the police — and urged a regional summit "as a matter of urgency." Not that their concern is likely to bring a deal any closer. MDC secretary general Tendai Biti told a press conference Tuesday: "We won an election. We will not accept a bad deal." A top Zanu-PF official who refused to be identified, countered: "The MDC wants power transfer rather than sharing. They want to reverse everything done by comrade Mugabe. They come with a vindictive approach."

The ruling party appears unable to shake the belief that its leading role in the struggle for independence entitles it to rule in perpetuity. "Zanu- PF is saying they liberated this country and that we should come into this deal as junior partners," said Biti. The Zanu-PF official all but confirmed that assessment, saying: "We will defend our gains."

Still, the rapidly worsening economic and social crisis may make it impossible for the ruling party to insist on maintaining its 28-year grip on power despite the verdict of the electorate, and increasingly, of landlocked Zimbabwe's neighbors. University of Zimbabwe political science professor Eldred Masungure was optimistic, arguing that although the process would take time, the end result is inevitable. "The reality in Zimbabwe is that there is political transition ... from authoritarianism to democracy. There is bound to be resistance from some quarters but that will end. This beyond the political operators. It is not stoppable."

(Click here for photographs of political tension in Zimbabwe)