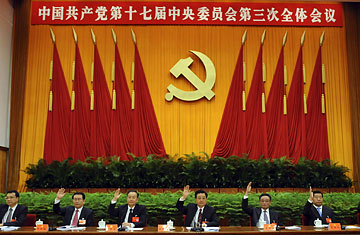

The third Plenary Session of the 17th Communist Party of China Central Committee on Sunday, Oct. 12, 2008 in Beijing

As the financial crisis has worsened in recent weeks, hopeful eyes have turned for help toward China, the newest major player on the world stage — and a country that is sitting atop some $2 trillion in foreign reserves, a cash hoard that some economists and U.S. officials believe could be instrumental in shoring up the battered balance sheets of the world's banks.

But true to form, China has so far kept its cards close to its chest. Prime Minister Wen Jiabao has pledged that his country would "join hands" with other nations in solving the crisis. But the ruling Communist Party held its Third Plenum in Beijing over the weekend. The meeting is usually an occasion for major policy decisions, but there was no word of what the top cadres' attitude to their country's role in the ongoing crisis might be.

Indeed, those looking eastward for a white knight must have been disappointed by the words of Yi Gang , deputy governor at the People's Bank of China, the country's central bank. Speaking at the International Monetary Fund meeting in Washington on Oct. 11, Yi blamed the crisis on "weak financial-policy discipline" by Western countries and said that they should be the ones to fix the problems they had created. "The major reserve-currency-issuing countries should shoulder the responsibility for preventing further spillovers and minimizing shocks to other countries," Yi said.

Still, China must realize that it is too deeply involved in the global economy to merely sit on the sidelines while the financial system unravels. It can't afford to. China has bought up some $1 trillion in U.S. debt, making it a major financier to the American credit binge. There have been longstanding fears that Beijing would at some point stop buying U.S. Treasury securities. That is unlikely because it could spark a selloff that would cause the U.S. dollar to plunge in value, eroding China's huge dollar holdings. Besides, China is still earning billions a day through its exports and "has to do something with the money," says one senior Beijing economist who asked not to be named. He and others note that a sudden move into the euro is highly unlikely with European economies looking weak and exchange rate losses threatening.

That doesn't mean that Beijing will be writing a blank check for Washington as it begins the process of raising the $700 billion the Treasury Department has been authorized to borrow to stabilize markets. As Beijing-watcher Will Wo Lop Lam wrote recently, Chinese leaders are expecting the U.S. to make large concessions in exchange for Beijing's financial support. These concessions may include guaranteeing Chinese investments in the U.S. (such as the roughly $300 billion of Fannie and Freddie May debt it owns). Demands could extend to non-financial areas. Beijing protested recently after the U.S. stationed a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier in Japan, for example. Chinese officials could even pressure Washington to halt weapons sales to Taiwan.

What China will likely not do is buy direct stakes in troubled banks, says economist Arthur Kroeber of Beijing-based Dragonomics consultants. "They have been burned already and will be very cautious," Kroeber says, referring to previous multibillion-dollar investments in companies like Blackstone and Morgan Stanley that have plunged in value. On Oct. 6, Ping An, one of China's largest insurance companies, announced it was forced to take a $2.3 billion write-off on an investment it made in the ailing Dutch-Belgian financial giant Fortis.

Economists say China's peculiar combination of unbridled capitalism and top-down state control has walled off the country's banks from most of the potentially harmful effects of the crisis. Although the country's membership in the World Trade Organization has required it to open its financial services sector to global competition and investment in 2006, "there is still only a narrow range of derivative instruments and innovation in financial products is still slow," says Sun Fei, Managing Director and Chief Economist at Hong Kong-based fund manager China International Capital. In other words, China's financial sector is just primitive enough to have prevented its banks from getting burned by buying complicated and ultimately toxic subprime mortgage products and derivative securities.

China's export-driven economy will suffer in a global slowdown, but the country is in a better position than many to ride out the storm, argues Kroeber of Dragonomics. "Commodity price are falling, reducing the price of manufacturing. And in any case, China makes the things you buy in Wal-mart and people will keep shopping there. It's countries that produce more high-end goods that will be worse affected."

Still, Kroeber and others stress that China may choose not to participate in a global bailout because leaders will have their hands full at home. Tougher economic times could affect the country's social stability, meaning leaders will direct their focus inward. "China's resources are strong enough to ensure its own economy can sail through this relatively smoothly," says Kroeber. "But they can't save anyone else's bacon."

(Click here for photos of life on the fringes of the People's Republic.)