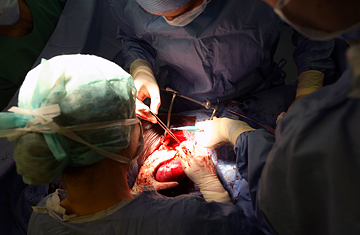

Surgeons perform a kidney transplant

Singaporean retail tycoon Tang Wee Sung could probably afford to buy almost anything. But in early July, Singapore authorities alleged that Tang tried to make an outré purchase: a new organ. Tang is currently charged with offering to pay a broker $220,000 to secure a healthy kidney from an Indonesian man.

Like every nation in the world apart from Iran, Singapore law forbids the buying or selling of human body parts. But with an acute shortage of donated kidneys and hundreds of ill people stuck on waiting lists, that could change. During a recent parliamentary hearing on two organ-selling cases, including the one allegedly involving Tang, Singapore's health minister Khaw Boon Wan said the city-state should consider legalizing the payment of kidney donors. "We should not reject any idea just because it is radical or controversial," he said. "We may be able to find an acceptable way to allow a meaningful compensation for some living, unrelated kidney donors without breaching ethical principles or hurting the sensitivities of others."

Singapore hasn't taken any definitive steps in that direction since Khaw aired the idea in late July. And though Khaw has said he was only bringing the subject up for discussion, his radical suggestion quickly provoked debate in Singapore's medical community. "It is not a good idea to legalize payment for organ donors as such payment institutionalizes the belief that the wealthy ill have property rights to the body parts of the poor," says Professor A. Vathsala, director of the adult renal transplantation program and head of nephrology at Singapore's National University Hospital. The Singapore Medical Association has also come out against such payment. (A Health Ministry spokesperson declined to comment on the issue).

Yet the idea of compensating living kidney donors also has prominent proponents in Singapore, who say that it could help solve a severe shortage — the waiting list for a kidney transplant in Singapore is up to nine years. Lee Wei Ling, director of the National Neuroscience Institute and daughter of Singapore founder Lee Kuan Yewm, last year proposed legalizing organ trading, arguing that if the donor was properly cared for and "if monetary incentive makes a potential living donor more willing to save another life, what is wrong in allowing that?" Khaw also proposed taking organs from older deceased people (the upper age limit for deceased donors now is 60), and encouraging more people to donate their organs after death. Those strategies have worked to shorten waiting lists in other countries like Norway and Spain, which has nearly doubled its donation rate in the last decade by training doctors to spot potential donors and by counseling families of the dead to consider donation.

But, to many in medical circles, the ethical line between actively encouraging organ donation and legalizing legalizing commerce in body parts is clear — particularly in Asia, which has both wealthy patients desperately in need of organs and desperately poor people who might be induced to part with them for money. The World Health Organization (WHO) opposes any commercial sale of organs, according to Luc Noel, a WHO coordinator for essential health technologies in Geneva. "It's been debated everywhere," Noel says. "Rich people have no reason to sell a kidney. That is the flaw that is unacceptable in any scheme involving purchasing a kidney: it's exploitative."

Anxiety about such exploitation by rich foreigners is already acute throughout Asia. In April, the Philippines banned kidney transplants for patients from overseas. In February, police in India broke up what they said was a black-market organ ring that may have taken as many as 500 kidneys from poor laborers and sold them to foreigners from the U.S., the U.K. and elsewhere. Even China, long a source of spare parts for foreigners willing to pay, has formally banned the practice and criminalized the sale of human organs for profit, according to Noel.

Singapore, like Thailand and Malaysia, is already heavily invested in medical tourism. In 2003, Singapore's government set up an agency specifically tasked with attracting foreigners to the city's state of the art hospitals. They've succeeded: according to a January report by Credit Suisse, Singapore hospitals treated around 200,000 foreigners in 2002. Last year, they treated more than half a million. At some of Singapore's best private hospitals, foreigners account for a third of total patients — and up to 40 percent of revenue.

Given that influx of wealth foreign patients seeking treatment, critics worry that legalizing the payment of organ donors could open a market for transplant tourism. "That sounds like a nightmare," says WHO's Noel. "I seriously do not think Singapore would like to create this image. They don't want to be the place where you can obtain the parts of another person."