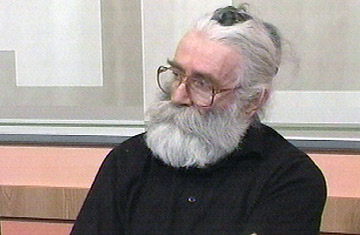

Former Bosnian Serb wartime leader Radovan Karadzic attends a conference under the false identity of Dragan Dabic on January 28, 2008 in Kikinda, Serbia.

It should have come as no surprise that accused war criminal Radovan Karadzic had no use for a lawyer once he was apprehended for trial in the Hague. Choosing to represent themselves is a time-honored tactic in trials where the accused reject the authority of the court and the legitimacy of the proceedings, seeing the trial instead as a platform for political protest. Gandhi did it; Fidel Castro did it; Nelson Mandela did it; and, more recently, so did former Yugoslavian President Slobodan Milosevic and accused 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

About 15,000 Serbian nationalists took to the streets Tuesday in Belgrade to show support for the former Bosnian Serb leader they consider a hero. Karadzic, awaiting extradition to the Hague, is facing a life sentence for genocide and crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). He is unlikely to fancy his chances of acquittal on some fine point of law that a better litigator than himself might be able to argue: "He has nothing to lose and wants to enter into history," says Mirjan Damaska, professor at Yale Law School, who is from Croatia and has practiced with the ICTY. "Frankly, if I was in [Karadzic's] situation, I would also defend myself."

In fact, choosing to conduct their own defense is a mechanism by which the accused can signal their rejection of the trial itself: "They don't recognize the authority of the court so they don't want to submit to its procedures in any way," says Alex Whiting, Harvard law professor who was a senior trial attorney at the ICTY and who worked on Milosevic's case. "And these are capable, strong people who are used to being in charge. They think they can do a better job of telling their story than anyone else."

"Pro se" defense, as it's called in the legal profession, offers the accused more than simply the opportunity to play the hero to their supporters back home and go down swinging — it can be a very effective means of delaying and disrupting proceedings, as the Milosevic trial amply demonstrated. Another pro se defendant, former Liberian strongman Charles Taylor, became so disruptive that the Special Court for Sierra Leone eventually forced him to use a lawyer. Similarly belligerent, Serbian nationalist Vojislav Seselj, also currently on trial in the Hague, had counsel imposed on him — but the appeals court overturned that ruling, allowing him to resume a pro se defense after he staged a four-week hunger strike that nearly killed him. "The court's greatest challenge right now is how to prevent Karadzic's trial from turning into a circus," says Cristian DeFrancia, a lawyer in the Hague.

Pro se defendants in highly politicized trials often succeed in slowing down the trial and skirting legal procedures because their very lack of expertise usually prompts judges to grant them more leeway than would be allowed a trained lawyer. "The defendants think — rightly — that because they are not lawyers they can say and do things that lawyers would not be permitted to say or do," says Yale Law School professor Steven Duke. "They can get information in that would otherwise not be there." While cross-examining a witness, for example, a pro se defendant can immediately rebut the testimony of a witness in a way that a lawyer simply cannot. The defendant might also hope that his antics provoke an error by the court or tribunal that ultimately requires a reversal — as has occurred in the Seselj trial — thus further postponing the ultimate decision.

The notion that the pro se defendant stands alone before the power of the court is, of course, a little misleading. More often than not, they avail themselves of the advice of lawyers following the case to help them build their defense. And lawyers are always available in the courtroom should the defendant change his mind and opt to use an attorney going forward. This way, counsel is ready to pick up where the defendant left off so there is no need to start the trial over.

The model pro se defense for Karadzic is presumably that of his old ally, Milosevic, who used the strategy to essentially take charge of his own trial and drag out the proceedings for four years until his death in custody. "He was able to use his self-representation to control the proceedings and turn it into a political show," says Whiting. Karadzic knows the trial will probably be televised in Serbia, which gives the erstwhile fugitive a bully pulpit from which to rouse his supporters back home. "The cost of self-representation is that trials will last longer and defendants get the chance to spread their ideologies," says Damaska. Which is why some lawyers have called for an end to self-representation at the tribunals altogether or at the very least, a tighter leash on defendants.

Although the technicalities of establishing the guilt of a political leader like Karadzic for the murderous actions of his followers can be legally tricky, the former Bosnian Serb leader, already 63 years old, may be assuming that he'll spend the remainder of his life behind bars. "Karadzic knows he can't defend himself against the most serious charges," says Damaska. "I don't think there is any downside to representing himself."