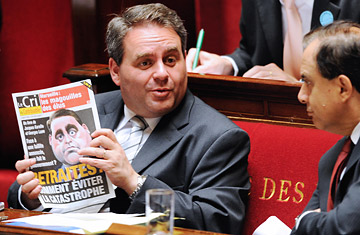

French Labor Minister Xavier Bertrand (L) holds a satirical newspaper during a parliamentary session to debate a government-backed law to ease the 35-hour workweek

France's ruling conservatives are celebrating the mothballing of what they've long derided as the most destructive legacy of Socialist rule: the 35-hour workweek. Late Wednesday, a government text gutting the left's decade-old labor innovation was voted into law, provoking cheers from rightist politicians that France Inc. could now better fulfill one of President Nicolas Sarkozy's key campaign slogans: "work more to earn more."

"Companies will at last be able to operate management policy based on a secure legal framework," Danièle Giazzi, a labor specialist for the ruling Union for Popular Majority party (UMP). "It's a remarkable advance for the economy." France's Labor Minister, Xavier Bertrand, the bill's author, hailed an "historic" revision of a law conceived by the country's "archaic" left, now in opposition. "It's the end of the imposed 35-hour week," he crowed.

Yet Bertrand's own wording belied a glaring incongruity in the law: while it allows employers to demand that workers spend more time at work, 35 hours remains the reference length of the French workweek. That's a smart move, since polls show the French are fond of the 35-hour week, and quashing it outright could prove unpopular.

Sarkozy's previous efforts to keep employees on the job longer relied on making overtime pay less costly to businesses and more profitable to workers. But that softer pitch was never popular with government officials and UMP members who saw the 35-hour week as an ideological red flag.

The new law lets companies ignore the nominal 35-hour maximum and negotiate — or impose — longer hours for staffers. In doing so, bosses will no longer have to worry about compensating extra time with days off, as they were previously obliged to do to keep any worker's average workweek over the year within the 35-hour limit. What's more, overtime work will no longer come attached to a 25% bonus, but with one as low as 10%, to be determined through negotiation.

Opponents of the new measures complain employers will now be able to impose non-optional overtime on employees, who would have to fear being fired if they refuse. They also expect businesses to stick to the lower-end 10% scale in paying for extra time, knowing that workers fearing for their jobs may not be able to stand up to their bosses for more money. That will be especially true in smaller companies, labor experts say, where staff organization and union representation don't match levels in bigger groups.

In any case, the new law means the de facto death of the 35-hour week introduced in 1998 with great fanfare and considerable controversy by the Socialist government of the day. The measure was designed to stimulate job creation by cutting up the pie of available work into smaller pieces. Socialists claimed the creation of 350,000 new posts in its first five years; similar numbers were provided by independent economists and organizations monitoring labor activity. However, conservatives have consistently accused the law of shackling French businesses and undermining economic growth. They've also noted that state subsidies softening the impact of the reduced workweek on businesses have cost taxpayers billions. The new legislation, its backers say, will leave companies freer to demand more work from staffers when needed, and allow employees to heed Sarkozy's appeal to help lift the economy — and their own slumping purchasing power — by working more.

Thus far, lower-paid workers appear ready to do just that. Ironically, the new law looks more set to cramp the style of middle and upper managers, whose long work days and greater disposable income made them the 35-hour week's biggest fans. Under the previous scheme, most so-called cadres happily logged 12-hour days, knowing they'd eventually be compensated with days off as compensation, in some cases making three-day weekends routine and further extending France's five weeks of paid vacation. Not surprisingly, several hundred cadres were the only ones protesting as legislators voted to reform their cushy work arrangement into obscurity. In that way, the new law already produced one small labor miracle: it made private sector executives sputter with a rage normally seen only among militant public sector strikers.