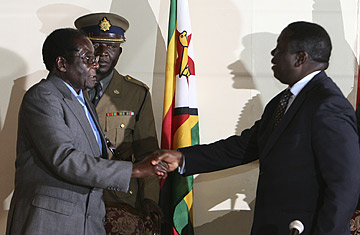

Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, left, shakes the hands of opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai in Harare on July 21

Monday's agreement on a framework for negotiations signed by Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai is hardly a rescue plan for the troubled southern African country, but it's certainly a start. "We sit here in order for us to chart a new way, a new way of political interaction," Mugabe said in Harare, after his first meeting in years with Tsvangirai — the man who finished ahead of him in the March 29 presidential election, only for Mugabe supporters to unleash a wave of violence that prompted Tsvangirai to withdraw from a runoff, which Mugabe then won uncontested. "We must act now ... as Zimbabweans, think as Zimbabweans and act as Zimbabweans."

For his part, Tsvangirai said it was time to leave "bitterness" in the past. "We are committed to ensuring that the process of negotiation becomes successful," he said. "We want a better Zimbabwe." Details of the agreement, brokered by South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki, were not immediately available. Mbeki said only that it "commits the negotiating parties to an intense program of work to try and finalize the negotiations as quickly as possible. All the Zimbabwean parties recognize the urgency of the matters they are discussing."

Mugabe has been unrepentant about the violence his regime orchestrated against opposition leaders and supporters. But condemnation of his handling of the election has come not only from the Western powers against whom he loves to rail but also from some of Africa's most influential voices, such as Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni and South Africa's ruling African National Congress. That, and the unanimous rejection of the election result by three African vote-monitoring groups, appear to have given Mugabe pause. At his June 29 inauguration Mugabe unexpectedly raised the possibility of talks, such as he agreed to Monday, saying he wanted "consultations" between "diverse political parties" to minimize differences and "enhance unity and cooperation," and that he wanted them "sooner rather than later."

The importance of Monday's agreement should not be overstated. The deal signed in Harare, the details of which have been kept under wraps, is simply an agreement to negotiate. The proverbial hard part will be the vexed questions of power-sharing, guarantees against political violence and how to secure a deal that allows both parties to sign on without appearing to accept defeat. Mugabe hinted on Monday that there was, in fact, some agreement on the way forward, saying the two sides had agreed "our constitution as it is should be amended" — a hint that the parties may accept Mbeki's suggestion to create a position of Prime Minister for Tsvangirai, to balance Mugabe's presidency. A similar compromise earlier this year proved successful in ending the political violence that followed Kenya's contested election.

Replacement of Mugabe's regime, or at least a dilution of its power, is essential not only for democracy but also to save Zimbabwe's economy, now in its 10th year of recession, with unemployment at 80% and inflation at 2.2 million percent.

The fate of the negotiations may hinge on the issue that has dogged Mbeki's mediation efforts for more than a year: immunity for the regime's past crimes. Mugabe's regime has repeatedly cracked down violently on opposition groups in its 28 years in power, including the slaughter of thousands of supporters of a rival liberation movement during the 1980s. Since Mugabe never signed the Rome Statute that established it, the International Criminal Court in the Hague has no jurisdiction over him or leading figures in his regime unless the Zimbabwean government or the U.N. Security Council requests that the ICC act. But Mugabe and his lieutenants would also want to secure immunity from prosecution at home. That may be a bitter pill for Tsvangirai, who has watched the regime kill his supporters at will and who has himself felt the boot of Mugabe's repression on more than one occasion. But in the absence of any plausible means of shifting the power balance in his favor, the opposition leader may be persuaded to defer justice if doing so could bring peace and the easing out of Mugabe's regime.