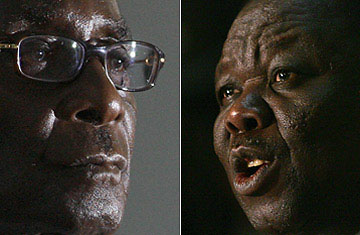

Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe, left, and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, right.

Despite Zimbabwe's opposition Movement for Democratic Change holding its first talks with representatives of President Robert Mugabe's government on Thursday, there's no early end in sight to the country's political stalemate. The meeting in the South African capital, Tshwane (formerly Pretoria), was aimed at pursuing a power-sharing agreement, to resolve the increasingly violent deadlock that has followed the widely discredited June 27 runoff election through which Mugabe claimed reelection following the withdrawal of the MDC's Morgan Tsvangirai amid a torrent of violence against his supporters. The talks reflect mounting international pressure on both sides to achieve a compromise.

Tsvangirai enjoys widespread international legitimacy for having won the country's first round of presidential elections on March 29, and the European Union has signaled that it will only recognize a Zimbabwean government led by the opposition leader. But despite having finished behind Tsvangirai in that vote, Mugabe holds the the key cards — the security forces and instruments of government are in his hands, and he has shown no qualms about using them to bludgeon his way back into power. There are no serious prospects for Mugabe being topped on the streets any time soon. In recent weeks, the opposition alleges, the state-sponsored violence that has gripped the country since March has escalated, with the regime now apparently bent on weakening its rivals to the point where they will be forced to accept the junior role in any new unity government.

Mugabe has said that he is willing to form a unity government, as has been demanded by the African Union. Without international recognition, Mugabe has precious little hope of reversing Zimbabwe's economic free-fall, and the international community is insisting that the opposition's election victory be recognized. But Mugabe's terms for unity are that the opposition must first recognize him as President. And he appears willing to use his monopoly on the instruments of violence to press his case — his supporters are currently focusing their violence against MDC parliamentarians, who won a legislative majority in the March election but are now hiding in fear of their lives.

"In the short term,from a power perspective, the current Zimbabwe elite is holding the cards," says Steven Friedman, director of the Center for the Study of Democracy in Johannseburg. "It's essentially trying to find a way to appear to be giving up some power, while keeping it all." To some, the fact that the MDC is even talking to Mugabe right now shows the limited options available to the opposition. Tsvangirai had last weekend shunned talks with Mugabe and South African President Thabo Mbeki, the African Union mediator the opposition accuses of being overly indulgent of Mugabe. Still, on Wednesday, MDC secretary-general Tendai Biti, who faces charges of treason, was given back his passport by a court order so that he could attend the talks in South Africa. "The onus is now on Morgan Tsvangirai and the MDC to do what they can to be part of the process if they want to, not the other way around," says Norman Mlambo, a chief research specialist at the Africa Institute of South Africa.

The MDC's vacillations about whether or not to negotiate with Mugabe reflect tensions within the party over whether to seek a quick end to the political crisis, or to pursue a longer-term strategy, says Friedman. "I think they are participating in the talks because of this dilemma," he says. An MDC source told Reuters that the talks were only a precursor to real negotiations: "This is where we are going to talk about issues of violence, and it is from these discussions that the MDC will decide whether to engage in full negotiations," the source said. The MDC's key terms for a unity government are an end to violence in order to allow fresh, credible elections.

Although the international community has vociferously denounced Mugabe's regime as illegitimate — and this week the G-8 agreed on a sanctions package to present to the UN Security Council (although Russia appeared later to backpedal) — only Zimbabwe's neighbours are in a position to apply direct pressure on the regime. And while support for Mugabe is waning within the Southern African Development Community and the African Union, the latter body still insists that the solution to the crisis is a government of national unity, rather than a transitional government to prepare for fresh elections. And that leaves Mugabe plenty of wiggle room. Sanctions, meanwhile, are more likely to hurt ordinary Zimbabweans than the regime, analysts say, and make them even more dependent on the state. The leadership would, however, feel the pain if their access to foreign exchange was cut.

As gloomy as the MDC's short-term prospects appear, some argue that they will improve rapidly as the isolation of Mugabe's regime grows — for the simple reason that without the support of the opposition, Mugabe will be unable to avert his country's economic collapse. With inflation estimated to at least 2 million percent, there's a growing prospect that mounting discontent among the rank and file of the security forces could destabilize the regime. At some point, says Friedman, the rate at which violence damages the opposition will be eclipsed by the impact of economic collapse and political pressure on Mugabe.

"I think the regime is in more of a fix than the MDC is," says Francis Kornegay, a senior researcher at the Center for Policy Studies in Johannesburg. "With time, the upper hand and the advantage tilts more towards the MDC, and it's a question of how they use that advantage."