Thailand's opposition launched a no-confidence motion against Samak, whose office remains under siege from hundreds of street protesters.

Forget about any honeymoon. Just four months into his tenure, Thailand's Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej is battling for his political life. For more than a month, thousands of street protesters have rallied in Bangkok, even besieging Government House last week and forcing the 73-year-old P.M. to sneak to work through a back door. On June 27, the veteran politician, who also moonlights as a television chef, suffered the indignity of a parliamentary no-confidence vote; although Samak's six-party coalition, which controls two-thirds of the lower house, shot down the motion by a vote of 280-162, there's no end in sight to Thailand's political crisis. Investors, spooked by the continuing turmoil, have fled the Thai stock market, which has swooned more than 10% since the anti-government protests began in late May.

Sunny Thailand may once have been a political bright spot in a region overshadowed by autocrats and juntas, but the last few years have been nothing short of chaos. In September 2006, after months of street protests against elected Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, the military deposed him in a bloodless coup. (Thaksin, a billionaire tycoon, was subsequently banned from politics and now faces corruption charges, which he denies.) A year of uninspired army junta rule followed. In elections last December, voters, who had once handed Thaksin the largest mandate in recent Thai history, brought to power right-wing firebrand Samak, who through his People Power Party (PPP) openly campaigned as Thaksin's proxy. Although Samak has in recent weeks distanced himself from his polarizing predecessor, his cabinet teems with Thaksin acolytes. Thaksin's former spokesman is now Foreign Minister, while his brother-in-law is deputy prime minister. Three wives of men who were members of Thaksin's now-banned political party have also ascended to cabinet positions.

The Thaksin effect pleases rural voters, who were charmed by the former P.M.'s populist health-care and micro-financing policies. But members of Bangkok's middle class and élite, many of whom were angered by a tax-free $1.9 billion business deal that Thaksin and his family profited from while he was in office, are rather less happy. The military, which went to the trouble of toppling him in 2006, surely is also irate over Thaksin's lingering shadow. (Thaksin himself has said he's done with politics, although his avowals have been rather less strenuous of late.) "It's a no-win situation for Samak," says Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a political scientist at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. "If he stands for Thaksin, then he's seen as a stooge and that hurts his personal honor. If he distances himself, then he alienates Thaksin's support base, which is the reason he's in power in the first place."

The question of just how involved Thaksin and his dissolved political party are in the current government dominated this week's censure debate. Specifically, the opposition Democrat Party hinted that Samak was conniving to dismiss the corruption charges filed against Thaksin. But the criticism of the P.M. wasn't limited to his relationship with his predecessor. The Democrats also charged that Samak has mismanaged the economy and dented national sovereignty by supporting Cambodia's bid to procure UNESCO World Heritage status for an ancient Khmer temple located on land some Thais believe is theirs.

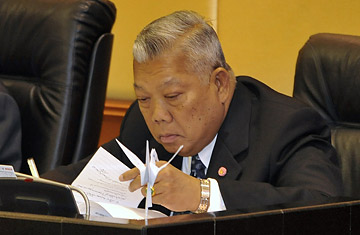

On occasion, the no-confidence sessions veered close to political farce. A member of the opposition Democrats accused Samak of being "immature" and "verbally and mentally dysfunctional." During the heated debate over his political future, Samak showed his disdain by pointedly folding origami cranes. He responded to the charges of mental incompetence by countering that he went for a medical check-up every three months — and that doctors had found nothing amiss.

Seven members of Samak's cabinet also faced no-confidence motions; all of them survived the vote. But the fact that the ruling coalition held together doesn't mean that Thai politics are returning to normal. Coup rumors abound. Street protesters vow to continue their rallies, especially if Samak continues with plans to scrap the constitution passed by Thailand's military rulers last year. One of the most contentious parts of the charter is a provision that a political party can be dissolved if one of its executives is convicted of wrongdoing. In February, Thailand's election commission found the PPP's deputy leader, Yongyuth Tiyapairat, guilty of vote-buying. That ruling could eventually lead to the entire party's disbanding. Samak would then be forced to resign.

It's no coincidence that one of the first constitutional amendments the P.M. pushed for is a reversal of the party-dissolution rule. Speaking to TIME, Samak scoffed at the possibility of a court case derailing his leadership and vowed to serve out his four-year term. But Thaksin is the only elected Prime Minister in modern Thai history to complete a full term. Unless Samak can channel Thaksin's once-mighty political skills, the occasional TV chef may be returning to stirring the wok full-time.