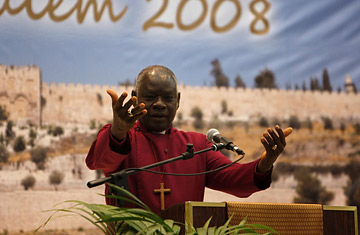

Archbishop Peter Akinola of Nigeria of the Anglican Communion speaks during the Global Anglican Future Conference opening session in Jerusalem June 22, 2008.

The would-be Anglican rebels gathered with storm clouds brewing around them. But now, even though the conservative Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFcon) has not concluded its meeting in Jerusalem, the secession it threatened to bring to the 78 million-member Anglican Communion looks like a confused bust.

This all comes as a bit of surprise to the press, which — with ample encouragement from the Church's right — had been framing GAFcon as a decisive step toward schism in the Anglican Communion, the third biggest global religious fellowship. GAFcon seems to be falling apart on several fronts. First came the venue problems: the conference ping-ponged embarrassingly at the last minute from Jerusalem to Jordan and back to Jerusalem.

Then there was attendance. The clerics at GAFcon were really supposed to sit out the Communion's once-a-decade Lambeth Conference in July. But it turns out several key conservatives did not even show up at GAFcon (or simply made brief appearances) and will go on to the church-wide meeting in Canterbury in July. Meanwhile, conservative Southeast Asian bishops have fallen out with some GAFcon leaders. The conservative conference now seems reduced mostly to Africans and some first-world ideologues, not all of whom are as gung-ho as Nigerian Archbishop Peter Akinola, the meeting's prime mover. Cheered on by several influential U.S. churchmen, Akinola has ridden high for several years as the point man for the ambitions of Anglicanism's populous, conservative "Global South" movement and for widespread outrage at the consecration of openly gay bishop V. Gene Robinson by the Episcopal Church of the U.S.A.

GAFcon's message was scrambled from the get-go. An opening statement by Akinola castigated "apostates" within the Communion and included the firebreathing line, "There is no more any hope, therefore, for a unified Communion." But he subsequently admitted in a speech, "We have no other place to go, nor is it our intention to start another church." Sydney Australia Archbishop Peter Jensen, a rising conservative, told reporters in Jerusalem yesterday that GAFcon "is a coalition of people who would not necessarily work together. Will it work? We don't know." Other speakers have been similarly vague.

Jim Naughton, an outspoken canon with the liberal Episcopalian Diocese of Washington, D.C., had been predicting a GAFcon meltdown for months. He feels that Akinola began losing influence at last year's meeting of Anglican archbishops in Dar es Salaam in February 2007. There Akinola pressed for formal approval of a new, conservative branch of U.S Anglicanism competing with Episcopalianism, a prototype of which he has already created. The move was seen as a harsh slap at the Communion and had the effect of reminding each primate that if schism occurred he too could be subject to such competition on his own turf. "People began to see that and fear," Naughton says.

Naughton's next tea leaf came last fall when a relatively moderate bishop defeated Rwandan hardliner Emmanuel Kolini to succeed Akinola as head of the African Anglican group CAPA. "Even within Africa," argues Naughton, "we saw the emergence of a large group of bishops who disagree with Episcopal Church on homosexuality but think Akinola and his American friends present a far greater threat to the Communion."

In the months before GAFcon, says Naughton, a leading Southeast Asian theologian criticized some of the planning of the conference. That elicited a scathing reply from one of Akinola's U.S. bishops. When that became public, conservative unity seemed suspect. Meanwhile, allegations in The Atlantic magazine that participants in an anti-Muslim massacre in Nigeria had worn tags with the initials of a Christian organization run at the time by Akinola contributed to the devaluation of his leadership. That loss of stature was further accelerated this week by the unwillingness of both Akinola and his Ugandan ally Archbishop Henry Orombi to condemn the alleged rape and torture of gays in their countries. Australia's Jensen had to step in with a blanket condemnation.

Naughton believes that the combination of Akinola's problems and a tension between conservatives more concerned about gays and those who increasingly regard that issue as a sideshow have combined to stall their movement, at least for now. "They overplayed their hand, and the tide has turned against these guys," he says.

Kendall Harmon, a canon with the diocese of South Carolina and in many ways Naughton's conservative counterpart, continues to hope that GAFcon may be the start of "a new thing." But Harmon agrees that GAFcon will not have the impact some had hoped for, and that barring a surprise conservative rebellion at the Lambeth conference, the big blow-up around homosexuality many had expected this summer will be deferred. Anglicans, says Harmon ruefully, are incrementalists, and "that has continued through this season."

This is good news for the survival of the Communion and bad news for the resolution of its tensions. It may slow down the defection of conservative Episcopal parishes, but probably won't stop it. It is also an object lesson for anyone who believes predictions of rapid change in a Communion whose strength former Archbishop Desmond Tutu reportedly described thusly: "We meet."