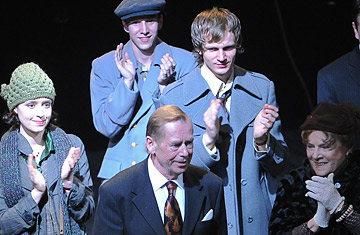

Playwrite and former Czech President Vaclav Havel, front center, is applauded by actors and audience after the world premiere of his new play "Leaving," Prague, Czech Republic, May 22, 2008.

Vaclav Havel insists that his first play in 20 years, which opened to enthusiastic reviews at a small experimental theater in downtown Prague on May 22, is not autobiographical. It's true that the play, entitled Leaving, and has echoes of Shakespeare's King Lear, tells the story of a top official leaving office —as former President Havel did in 2003. Some of its characters seem easily recognizable to those familiar with Czech politics. But Havel is not being disingenuous: The lead character, an aging politician named Vilem Rieger, is far too humorless to represent the former dissident who once scored Lou Reed an after-dinner gig at the White House. "I was interested in the more existential side of things," Havel told reporters in Prague this week. "I thought it was interesting how when someone loses power he can also lose the meaning of life."

Havel may not be recounting his own life story, but he is clearly drawing on his experience as one of the leading figures of Eastern Europe's democratic transformation. Czech audiences are being offered a rare perspective on a pivotal period in eastern European history. So far, they appear to like what they see. The 71-year-old playwright attended the opening with his actress wife (who was originally cast in the play but dropped out at the last moment) and received a 10-minute standing ovation. He thanked the audience quickly and then rushed off stage.

Friday's newspapers treated the event as if it were a soccer cup final. "What is Havel's Play Like?" runs a bold-type headline followed by five stars in Lidove Noviny, a daily not in the habit of running arts stories on its front pages. The business daily Hospodarske Noviny called the play the "theatrical event of the season" . "Sure, the fame of the author � plays a role but it is an extraordinary experience nonetheless."

Reviewers are praising the play for its artistic and historical sweep; allusions range from Shakespeare's King Lear to Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, and the troubled history of the Czech republic. An English version is scheduled to open in London in September .

Leaving is the latest in a clutch of recent works shedding light on the inner life of the erstwhile dissident. A memoir titled To the Castle and Back was published in English translation last year, while Citizen Havel, a new documentary about his life in office, has been warmly received at film festivals across Europe.

Havel became known to the world as the leader of the "Velvet Revolution" that peacefully ended Communist rule in what was then Czechoslovakia, although he'd been active in dissident politics in the former Warsaw Pact state since the 1960s. He served two terms as president but somehow managed to maintained a reputation as an affable, reluctant head of state. In the early days of his Presidency, he invited jugglers and street performers into the presidential residence for "a festival of democracy" to exorcize the demons of communism.

In fact, he began writing Leaving in 1989, but set it aside and completed it only in 2007, after retiring from politics. Havel often said that he hoped to keep his artistic and political lives separate. His new play is proof of how ultimately he failed to do so. But, for many theater goers and readers, that's a blessing. Leaving documents the fall from grace of a powerful man. It takes an uncompromising, knowing look at the greed and excess that followed the fall of communism — a period that tends to be mythologized in the West. As an icon of that revolution, no one is better placed to reconstruct it.

An ambitious character named Vlastik Klein (whom some commentators speculate is modeled on Havel's political rival, current president Vaclav Klaus, although he differs from Klaus in important ways) embodies the materialistic, mobster-driven world of eastern Europe in the 1990s. Klein slyly ousts the Chancellor from his government villa, then buys it himself and converts it into a shopping mall complete with brothel. The language makes light of democratic institutions. "A good leader must be surrounded by a good network of think tanks," Rieger says at one point, using the English for 'network' and 'think tanks'.

Havel's memoir and the documentary on his tenure offer a similarly nuanced view of fledgling democracies, capturing the boyish excitement of a new world together with its absurdities.

Havel is famous in the Czech Republic for his understatement. But his friends and colleagues know him more as a behind-the-scenes master of ceremonies. In Leaving, for example, he includes himself in the play not as a character but as a kind of chorus. Interlaced throughout the script are comments about the creative process which director David Radok has Havel himself voice as the actors freeze on stage. The effect is odd, at first but, in the end adds a fitting layer of ironic detachment. Characteristically, Havel's main stage direction during the play is to tell his actors not to overact. On opening night, in the final scene, after the cast exits back stage on a elevator-like device rising skyward, leaving the theater hauntingly still and dark, Havel's gravelly voice boomed out over loudspeakers. "I thank the actors for refraining from burlesque," he said. "The theater thanks the audience for switching off their cell phones. Truth and love must triumph over lies and hatred! Turn on your cell phones. Good night and sweet dreams!" The audience stood and roared.

—With reporting by Katerina Zachovalova/Prague