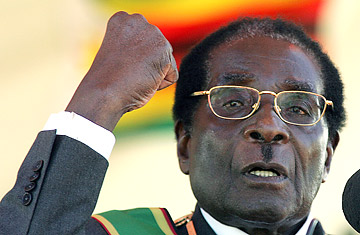

Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe addresses a crowd, April 18, 2008.

Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe appears increasingly unlikely to allow the election he appears to have lost to end his 28-year tenure. Zimbabwe Electoral Commission officials on Sunday announced a new delay in the recounting of votes from 23 of the 210 constituencies in an election held three weeks ago. Opposition leaders believe the results are being rigged to deny them victory, but the growing campaign of violent intimidation against opposition supporters makes it unlikely that the opposition would take matters to the streets. So the search for a resolution to the crisis has increasingly shifted the spotlight to the landlocked country's neighbors, and the extent to which they might pressure Mugabe to respect the electorate's verdict.

Opposition presidential candidate Morgan Tsvangirai has fled the country, while 10 opposition activists have been killed and hundreds more injured in post-election violence — and refugees continue to stream across the border into South Africa. Despite growing calls from around the region and the world for the immediate release of the election results, Mugabe appears unmoved. Last Friday he celebrated the 28th anniversary of Zimbabwean independence by aiming his wrath against Britain, the former colonial power, whose bidding he accuses the opposition of doing. "Down with thieves who want to steal our country," he thundered, in his first speech since the elections, calling on Zimbabweans to be vigilant "in the face of vicious British machinations and the machinations of our other detractors, who are the allies of Britain."

While Britain bluntly accuses Mugabe of "stealing" the election, reactions from African leaders have been more restrained. On Sunday the African Union joined the chorus of calls for the immediate release of poll results. Former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan also weighed in, calling on African leaders to find a solution to the situation, which he called "a serious crisis with impact beyond Zimbabwe." But leaders of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) kept noticeably quiet on Zimbabwe at a summit on poverty and development being held in Mauritius — except to ask South African President Thabo Mbeki to continue to lead mediation efforts on their behalf.

South Africa is the neighbor with the most leverage over Zimbabwe because of economic ties, but President Mbeki has stuck fast to his policy of "quiet diplomacy," refusing to apply visible pressure on Mugabe. Still, Mbeki's political marginalization within his own party, which made him a lame duck when it chose his arch-rival Jacob Zuma as ANC president last December, has emboldened critics of his Zimbabwe policy. Trade union members in the South African port of Durban refused to offload a Chinese ship carrying armaments for the Zimbabwean government. The vessel, having also been denied entry to Mozambique and Tanzania, had to leave the port and may be recalled to China, according to news agencies. And Zambia's President Levy Mwanawasa took the unprecedented step of urging surrounding countries not to allow the cargo of weapons to reach Zimbabwe for fear of escalating the crisis.

Analysts believe that only Zimbabwe's neighbors, particularly South Africa, have the leverage to force Mugabe to resolve the crisis. But Zimbabwe's neighbors are divided among themselves over how to respond, and all are wary of an anarchic breakdown that brings thousands more refugees streaming across the border. Although Mugabe has long traded on his credentials as an anti-imperialist liberation hero, younger leaders in the region are exasperated by Mugabe's behavior. On Friday, Botswana's foreign minister, Phandu Skelemani, broke ranks with his SADC peers to publicly criticize Mbeki's handling of the crisis and admit that leaders are more concerned about the situation than is reflected in their public statements.

Referring to the extraordinary SADC summit called the previous weekend to discuss Zimbabwe, he said: "Everyone agreed that things are not normal, except Mbeki... But now he understands that the rest of SADC feels this is a matter of urgency and we are risking lives and limbs being lost. He got that message clearly." Still, Mugabe can count on a more sympathetic hearing from such liberation-era stalwarts as Angola's President Eduardo Dos Santos.

Although Mugabe may be vulnerable to pressure from his neighbors, analysts doubt that member states of the SADC will agree on any decisive action that could force him to go. South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki and other leaders have previously given Mugabe political cover by endorsing the results of previous elections that have looked questionable to international observers. "The one thing Mugabe has been able to do is rely on the support of the region," says Elizabeth Sidiropoulos, national director of the South African Institute for International Affairs. "So, the question is, at what point do Mugabe and the [Zimbabwean] security forces think that the tide has changed?"

South Africa holds the ultimate leverage over Zimbabwe, because, as the country's electricity supplier, it could simply turn out the lights. But shutting down Zimbabwe would be considerably more painful for Mugabe's long-suffering people than for the aging autocrat himself, and the resulting refugee crisis would put a destabilizing strain on both South Africa and other neighbors. Yet Chris Maroleng, a Zimbabwe expert at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria, expects that regional leaders will toughen their stance in time. "Following the recount [of votes in Zimbabwe], we will probably see some kind of cohesive strategy to deal with Zimbabwe," he says. "As the situation worsens in Zimbabwe, [regional leaders] will increasingly see Mugabe as a liability." That, and the precarious state of Zimbabwe's finances, may yet change the country's political calculus.