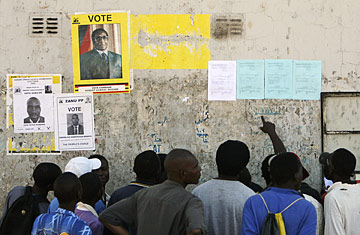

Zimbabweans look at preliminary election results on a wall in a suburb of Harare on March 30

In the Harare township of Warren Park, for the first time that anyone can remember, political graffiti has begun to appear on clapperboard walls and the backs of tin sheds. Alongside election posters for Robert Mugabe, unseen hands scrawl messages to the President. "Chinja Maitiro" reads one: "Change Your Way." Another declares: "Zuakwana," meaning "Enough." Nearby, a picture of the 84-year-old Zimbabwean leader has been defaced with blood-red tears and underneath is written the word: "Cheat." These are ominous signs for the despot who has ruled Zimbabwe for 28 years. But there are other, more urgent ones emerging elsewhere in the capital. The slow drip-feed of official results from the March 29 general election had shown, by Wednesday, that Mugabe's Zanu-PF party had lost its parliamentary majority as the opposition tally reached 105 of the 210 seats in parliament, compared with 94 for the ruling party. The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, staffed by Mugabe loyalists, has not released the presidential results, although the state-run Herald newspaper acknowledged that Mugabe had failed to win on the first round, and predicted a run-off against Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The MDC, meanwhile, released its own tally of the vote from lists posted outside polling stations, and claimed that Tsvangirai had scored an outright victory with 50.3% of the vote.

If this were a normal democracy, Mugabe would have been turned out years ago. He has presided over a social and economic crisis that has seen unemployment reach 80% and inflation at more than 100,000%, while average life expectancy has plunged to 34 for men and 37 for women. Mugabe had tried to deflect attention from his own failings by championing the confiscation and redistribution of white-owned farms — the legacy of a colonial past that had left the lion's share of arable land in the hands of Zimbabwe's white minority — but this only deepened the crisis: The pick of the confiscated farms went to the President's cronies, and the country that had once been the bread-basket of southern Africa was suddenly no longer able to feed itself.

That is a lot more than most electorates would stand for, but Zimbabweans had little redress. After the 1980 election that ended the white minority regime of Rhodesia and brought him to power, Mugabe created a kind of one-party democracy, in which elections and nominally independent state institutions were dominated by his Zanu-PF party, which beat opponents and rigged ballots, and where the organs of state, particularly the army and police, were loyal to the party rather than the people. Left with no means of redress as their homeland rotted, millions of Zimbabweans simply left the country.

As the weaker candidate with none of the MDC's momentum and little chance of picking up support from other losing candidates, Mugabe would be extremely unlikely to win a free and fair run-off vote. In the past, that fact alone would have been a cue for repression and rigging. But this year's relatively violence-free campaign suggests many soldiers and policemen are no longer so willing to do their President's dirty work. The MDC still claims the regime fixed many parliamentary seats. But reports in the government's primary organ, the Herald, indicate that the regime has accepted that Mugabe failed to win.

Dictators are rarely eased out gracefully, and Mugabe's departure now seems a matter of time. "It's the beginning of the end for Mugabe," said Aubrey Matshiqi of the Johannesburg-based Centre for Policy Studies. At a Harare press conference on Tuesday, Tsvangirai declared: "After Saturday, March 29, Zimbabwe will never be the same again. The votes cast on Saturday were for change and a new beginning." Mugabe's exit, whenever it comes, would cue the rebirth of a nation.

Zimbabwe's regeneration, says Michelle Gavin, Adjunct Scholar on Africa at the Council on Foreign Relations, "would have to be an all-hands-on-deck effort." International financial institutions and donors, which ended their involvement to protest the regime's corruption and human rights abuses, would be likely to step in with emergency programs to bring Zimbabwe back from the brink. And already international investors sense a bargain in the making. LonZim, an investment fund set up by the Lonrho mining group last December, has already raised $65 million to invest in Zimbabwe. "We're very bullish that Zimbabwe as a country will become very strong again," said LonZim director Geoffrey White. "Any economy that is in the position that Zimbabwe is in will recover. That's the opportunity." Zimbabwe retains a solid base of infrastructure, and considerable mineral deposits.

For Mugabe himself, the future may be less rosy. Leaving office might well earn him a day in court to answer for some of his actions, particularly the Matabeleland massacres in which tens of thousands of people were killed after Mugabe ordered his army's North Korean-trained Brigade 5 into the heartland of Mugabe's longtime political rival, Joshua Nkomo. But Mugabe may be smarter than other strongmen, such as Liberia's Charles Taylor, who were eased into exile with a promise of immunity, only to find themselves on trial at The Hague. A spokesman for the International Criminal Court, in a statement released to TIME, hinted that the Zimbabwean President ensured long ago that he would outwit international justice. "Zimbabwe is not party to the Rome statute [which created the court]," said the spokesman. "The court does not have jurisdiction over crimes allegedly committed in Zimbabwe or by Zimbabwe nationals." So, even when the writing is on the wall in Harare, Robert Gabriel Mugabe may still have a few last tricks up his sleeve.

—With reporting by Ian Evans/Harare and William Lee Adams/London