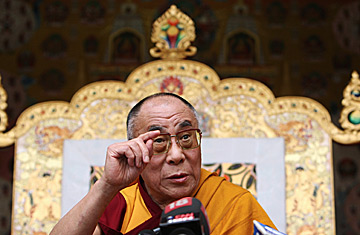

Tibetan spiritual leader His Holiness the Dalai Lama gestures while answering media questions in Dharamshala on March 16, 2008.

"China is strong because we are on our knees," read a big red banner held aloft by half a dozen youngsters with Tibetan flags painted on their faces, gathered at Dharamsala's central Tsulagkhang Temple early Sunday. As hundreds of Tibetans and their supporters streamed in, trampling over Chinese flags strewn along the way, more banners appeared: "This is the moment — now or never"; "Shall we be slave or be free?" Shouts of "Pogyalo" — Free Tibet! — rose up to express solidarity with a long-planned "Dharamsala to Lhasa" march that started on March 10, as hundreds of yellow and brown Tibetan flags fluttered in the wind. "We had hoped for this response," says Sherab Woeser, one of the coordinators of the march. "But now that the pent-up anger and frustration are out, we need to find a way to manage it."

Events since March 10 have marked a watershed for the thousands of Tibetans, mostly youngsters, who disagree with the Dalai Lama's moderation but have been conditioned to defer to their spiritual leader. While China's restrictions on the media make it extremely difficult to know what exactly sparked the uprising within Tibet, many young Tibetans outside their homeland feel it is time to stop being pushed around by Beijing. "His Holiness is a monk, he advises patience," says Nwawang, a 33-year-old chef who fled Tibet for India over 10 years ago. "But we can't leave things the way they are. We must act now before Tibet, our homeland, our culture is wiped out. And now is the time when the entire world is looking at China."

On Saturday, hundreds of young monks, nuns and ordinary Tibetans, furious at the Chinese crackdown in Lhasa, Tibet's capital, marched to Jwalamukhi, where an earlier group of marchers had been detained for 14 days by Indian authorities. Nearly 700 people had descended on the town by evening. Organizers of the original march feared that passions could get out of hand and had to turn the protestors away, telling them to remain non-violent. On Sunday, hundreds more people gathered at Tsulagkhang Temple. More marches are planned for the coming days.

The march to Lhasa, which started it all, was the brainchild of activists impatient with the "middle-path" approach. One of them, Tenzin Tsundue, now in detention in India, has been a longtime supporter of more fervent resistance. In 2002, he made news by scaling 14 stories of scaffolding of a Mumbai five-star hotel when Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji was inside. "Some would say there is a disconnect between young Tibetans and our political leadership, and that it would help if the Dalai Lama moved toward a sterner position — possibly say China better get serious about the talks or walk out," says Lhadon Thetong, executive director of the New York-based Students for Free Tibet. "Personally, I think all Tibetans minus 10 want independence."

Those ideas resonate in Nepal, home to another sizeable Tibetan population, where Tibetans have demonstrated daily for the past week. The protests have been broken up by Nepal's police, often violently, but that doesn't bother Tenzing Wangdu, 32, who was the president of the Nepali chapter of the Tibetan Youth Congress until a few months ago, and proudly shows off welts on his upper arm and back where the police clubbed him during yesterday's protest. "Having marks on your body makes you feel like you are among our brothers in Tibet who are giving up their lives." Tenzing Dolkar, 29, says all Tibetans would like to deal with China peacefully, but that the situation has gone beyond that. "At the moment the Dalai Lama is telling us not to shout and use violence against the Chinese, but the situation is such you can't always follow," she says, moments before a peace march around a Buddhist temple on the outskirts of Kathmandu. "So..." Her voice trails off and the sentence is left hanging.

The Dalai Lama told reporters Sunday that he continues to favor the "middle path" of autonomy within China rather than demanding full independence for Tibet. But if the momentum inside and outside Tibet continues for even a few more days, say protestors, it can continue for weeks. "We're working to make the occupation costly for China," says Lhadon Thetong, who remains committed to non-violence but is planning more protests in front of embassies around the world and is hoping to get as many protestors into Beijing during the Olympics as possible. "No one had a clue when the Berlin Wall came down," she says. "History is long, and only time will tell what will bear fruit."

— With Reporting by Simon Robinson/Kathmandu