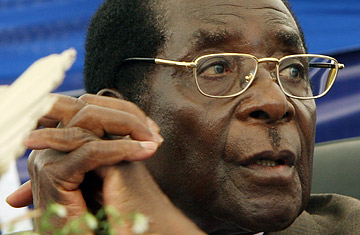

Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe.

As he celebrated his 84th birthday last week, Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe may have joined millions of his countrymen reflecting on the single question that has come to dominate his 27-year rule: How long can "Uncle Bob" go on? Democracy will not unseat him; the joint presidential and parliamentary election scheduled for March 29 will be neither free nor fair. The Zimbabwean army has orders to oversee the poll, while opposition politicians remain at the mercy of the police, and journalists are still subject to arrest. In fact, most Zimbabweans are too worried about finding their next meal in a country where the official inflation rate has passed 100,000% to concern themselves with challenging one of Africa's most enduring strongmen. Still, recent weeks have witnessed a series of events that suggest Mugabe is facing a concerted challenge from what, to outsiders, will seem an unexpected quarter: within his own Zanu PF party.

Earlier this month, former finance minister and Zanu PF stalwart Simba Makoni announced he would stand against Mugabe in the poll. Makoni is an unknown quantity: in office he had a reputation as a technocrat who tended toward moderation and pragmatism, but one who was also a fully paid-up member of the Mugabe machine. But the significance of Makoni lies less in what he is than in what he represents — a split in the ruling party. "There is a sense that this is a real opportunity," says Elizabeth Sidiropoulos, national director of the South African Institute of International Affairs, in Johannesburg, South Africa. "Mugabe's position is really being threatened." Lack of transparency and of a free press inside Zimbabwe has made it hard to pinpoint the direction of Zanu PF and, just as significantly, which party power brokers might be backing Makoni, she says, but "it appears as though a split is happening before our eyes."

Nor is Makoni's the only challenge to Mugabe. Sidiropoulos and Chris Maroleng of the Institute for Security Studies, also in Johannesburg, confirm reports from inside Zimbabwe that scores of Zanu PF members are standing as independents against their party's official candidates. "With a weak opposition, the best chance for change is a reconstituted Zanu PF," says Maroleng. "This election shows that there is significant indiscipline and disarray with the party, and efforts being made to achieve precisely that."

Maroleng says he has been told that leading Zanu PF figures such as former defense chief General Solomon Mujuru, former home minister Dumiso Dabengwa, and General Vitalis Zvinavashe, who succeeded Mujuru, are backing Makoni and the renegade Zanu PF candidates. (There has been no official announcement.) Arthur Mutambara, leader of a faction of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (M.D.C.) has also endorsed Makoni's bid, while Mutambara's M.D.C. rival Morgan Tsvangirai, who initially dismissed the former finance minister as "old wine in a new bottle," will meet Makoni to discuss a possible alliance, according to a report in the Harare-based Zimbabwe Independent on Friday.

The reason for rising discontent inside Zanu PF is not hard to guess. Not even their exalted status in Mugabe's machine can protect the Zanu PF leaders from the ravages of an economy that is collapsing as fast as any in history. Last week the government announced inflation had breached 100,000%, up from 66,000% in December. Industry, agriculture and the service sector have all but ceased to exist. Shops stock no food, and power cuts last for days. Between a quarter and a third of Zimbabwe's original population of 13 million are believed to have fled the country, the majority for neighboring South Africa. The only functioning part of the country is the security apparatus, but, aside from Mugabe's bodyguards, even that is now questionable, with consistent reports of no pay, sporadic mutinies and the apparent allying of some heavyweight military figures against Mugabe. "These guys have a bottom line," says Marengo, "and Mugabe is increasingly seen as an economic liability."

Few, however, discount Mugabe's shrewdness or his capacity for survival after 27 years in power. "With the implosion on his party," says Marengo, "Mugabe will continue to rely on the security establishment to ensure all decisions are done in his interest. He will resort to extra-legal measures. And given his history, you have to say that it is highly unlikely that Makoni will win." Nevertheless, the result will be keenly watched.

"People will make their moves based on the result," says Marengo. One key factor could be the degree to which the security services rig the vote, as normal, or the countervailing influence of Makoni, Mujuru and others can persuade them to stand aside. The London-based Zimbabwean newspaper even published a front-page story on Thursday detailing what it said was Mugabe's contingency plan to flee the country should his position become untenable after the poll. But most analysts agree such reports are more wishful thinking than fact. South African government and Zimbabwean opposition sources claim it is true, however, that the question of Mugabe's retirement — and a deal giving him immunity from prosecution for war crimes and genocide over the Matabeleland massacres of the 1980s — has long been high on the agenda of mediation talks, led by South African President Thabo Mbeki, between Mugabe's regime and Zimbabwe's opposition. "It's been a long, long beginning to the end," says Sidiropoulos, "and the lesson is: never underestimate the power of fear in totalitarian regimes. But the point remains: if you are able to remove Mugabe, however it happens, then that creates an opening for a return to normality."