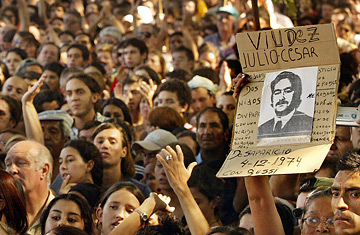

A demonstration in front of the ESMA, a navy building where Argentines were tortured during the 1976-1983 dictatorship.

In August 2003, Ana Careaga was jubilant. Argentina had just overturned two amnesty laws protecting military officers from prosecution for human rights crimes committed during its bloody 1976-83 dictatorship. "I thought justice would be done at last," says Careaga, a survivor of the Atletico death camp, where in 1977, at the age of 16, she was tortured at the hands of the military.

Careaga wasn't looking for justice for herself but for her mother Esther, who had been a founder of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, a group of women who in 1977 started marching every Thursday in front of the the presidential palace in downtown Buenos Aires, to demand news of their missing children. A captive of another death camp, Esther Careaga perished in a "death flight," thrown alive from a military plane into the waters of the South Atlantic, the preferred method of disposal of its enemies by the dictatorship.

But the hope of seeing sentences for such crimes handed down anytime soon is fading fast for Careaga and many other relatives of the over 20,000 people who "disappeared" during those dark years. Over four years after the repeal of the laws, only a handful of the 850 suspects protected by them have been convicted, as trials remain bogged down in endless pre-trial hearings and insistent appeals by defense lawyers.

"This is a continuation of the amnesty laws by other means," says Careaga. "The delays are inadmissible. If normal judges can't do the job, they should set up special courts to try crimes against humanity in Argentina." Careaga adds, "The crimes have been proven, the witnesses have testified over and over again" referring to years of pre-trial hearings.

The ardently pro-human rights administrations of outgoing President Nestor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernandez, who succeeds him in office on December 10, also find the long delay difficult to explain. "Judges tend to admit ridiculous appeals from defense lawyers that should be rejected outright for lack of merit," says Luis Alen, the lawyer at the government's Human Rights Secretariat in charge of monitoring the trials. "These constant appeals have slowed down cases going to prosecution for months on end, over and over again."

Victims of the dictatorship feel they are facing a denial of justice under the pretext of slow-moving trials. The murder of Careaga's mother, for example, first went to court after the return of democracy in 1983 but was cut short when the amnesty laws were passed in 1986-87. It was reopened in September 2003 as part of the block of cases involving the Navy's detention camp ESMA,including some 120 suspects and 5,000 "disappearances."

Only one ESMA case, involving a low-ranking Coast Guard officer named Hector Febres, has been sent to trial so far. "Febres is being tried on only minor counts regarding the abduction and torture of four people who actually survived," Alen says, shaking his head.

Ana Testa, a 53-year-old ESMA survivor who was kidnapped and tortured in 1979, directed harsh words at the judges on their dais when she testified at the Febres trial earlier this month: "I think 24 years is a long time to start a trial," she said. Some 130 suspects have died since the end of the dictatorship. "These murderers are laughing at all of us, at you judges, at the prosecutors, the lawyers," she told the bench. "They are dying without telling us the truth."

The government blames the delay on court officers still left over from the time of the dictatorship. "The ideology of many judges is similar to what it was 30 years ago," says a government source. "We are basically powerless because we can't remove judges just because we don't like their politics. Removing a judge is a slow, laborious process with strict rules." A source in the judicial branch denied the charges of sympathy with the old military dictatorship, saying that the delays are due to overworked and understaffed courts. "Even common crimes can take five or six years to result in a conviction in Argentina," said the court official who asked not be identified. "These human rights [cases] are much more complicated and require even longer."

But victims of the dictatorship say they don't want explanations, they expect results. "We are tired of hearing that justice is slow, that it is an independent branch; these judges are a rotten caste, something should be done for the removal of these judges," says an angry Testa.

And in a chilling reminder of Argentina's grim 1970s and 1980s, witnesses have had to deal with a constant barrage of anonymous threats. Or worse. One witness, Jorge Julio Lopez, disappeared in September last year after providing testimony that led to the conviction of former police officer Miguel Etchecolatz. There has been no news of him so far, despite a nationwide publicity campaign by the government.