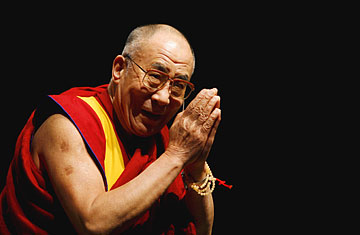

His Holiness the Dalai Lama of Tibet greets the crowd during a speech at the Civic Centre Arena in Ottawa, Canada, October 28, 2007

The announcement by Tibet's spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, that he might consider changing the centuries-old method of succession is a sign both of the exiled god-king's advancing years and his increasing desperation in the face of attempts by Beijing to aggressively pacify his homeland. In an interview with a Japanese newspaper, the 72-year-old Nobel Peace Prize laureate indicated that he and his aides were considering several methods that could replace the tradition of searching for a reincarnation of the Dalai Lama among Tibetan boys whose birth coincides with the previous incumbent's death.

"If the Tibetan people want to keep the Dalai Lama system, one of the possibilities I have been considering with my aides is to select the next Dalai Lama while I'm alive," he told the Sankei Shimbun in an interview published November 21st. That could mean either some kind of democratic election among senior Buddhist monks or a personal selection by the current Dalai Lama himself, who is the 14th of the line. For 13 successive incarnations, monks have fanned out across Tibet with relics of the deceased Dalai Lama to try and find his next incarnation — a boy who recognized the objects and thus signaled that the Dalai's soul had passed into a new earthly envelope. It is a ritual that both affirms and reflects the basic foundations of Tibetan Buddhism, reincarnation and the rule of a revered group of repeatedly reborn monks. That the protector of Tibetan culture would consider scrapping a core tenet of Tibetan tradition and possibly undermining his own legitimacy are sure signs that China is solidifying its dominant position in the decades-long standoff.

The Dalai Lama has had a number of international successes in recent weeks promoting his cause of Tibetan autonomy — not, he has taken pains to note, independence — and protection of its culture, much to Beijing's fury. He met with Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel in Bonn and soon after addressed both houses of Congress in Washington. President George Bush even presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award the body can bestow.

But despite those high-profile appearances the Dalai Lama is well aware that time is on Beijing's side. "The Chinese are simply waiting for him to die," says Nicholas Bequelin, a China researcher for the New York-based rights organization Human Rights Watch. When the Dalai Lama is gone, Bequelin says, supporters of Tibetan autonomy will have lost what is by far their most potent symbol of resistance to Chinese rule. Whoever takes over will have a much-diminished presence. History tends to back up that judgment. In 1995, the Dalai Lama chose a six-year-old Tibetan boy, Gendun Choekyi Nyima, to take the title of Panchen Lama, effectively the second-highest-ranking monk in the complex Tibetan hierarchy. The boy and his family disappeared almost immediately — spirited away, many suspect, by Chinese authorities — and haven't been heard from since. Beijing later appointed its own candidate for the position — a boy, now 17 years old, who was prominently on display as a guest during last month's 17th National Congress of the ruling Chinese Communist Party in Beijing.

To counter this, the Dalai Lama appears to have set on finding a suitable successor himself, one whose legitimacy is unsullied by unseemly squabbles over ritual with China and who has been handpicked to take up the advocacy work on behalf of his people once he dies. Making his succession an issue at this time may also be an attempt to tweak the Chinese — sensitive about their reputation in the walk-up to the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008 — into taking a more accommodating position regarding the Tibet issue. Unlike more radical Tibetans, the Dalai Lama has always advocated autonomy, not independence, from China; and he has always said that he admired Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic. Beijing, however, has consistently lumped the Dalai Lama with the rest of what it calls the "splittists," or those who would break up China.

But even if the Dalai Lama finds the perfect candidate, it may be too late. Beijing has become more sophisticated in dealing with Tibetan religion, allowing some interaction among less exalted lamas on both sides of the political divide. More importantly, the accelerating erosion of Tibetans' traditional nomadic lifestyle, along with a burgeoning influx of ethnic Chinese workers, businessmen and tourists, makes it likely that Tibet will lose much of its unique cultural identity within a generation. Bequelin points to the example of China's Muslim-majority province of Xinjiang, where Beijing has spent billions encouraging tourism — notably by building a train line through the region's vast desert to the remote city of Kashgar, connecting it with the rest of China — and improving the infrastructure to extract its considerable oil reserves. Along with the strict repression of even the slightest signs of dissent, the policy has been highly successful in neutralizing opposition to Chinese rule.

In Tibet's case, similar tactics are being used. A $5 billion train line connecting Beijing and Lhasa opened last July, doubling tourism arrivals in the region. A forced relocation program that will resettle tens of thousands of nomadic herders, along with increasing urban migration among young Tibetans, will ensure any remaining resistance dwindles with time. "It's never a pretty sight when indigenous peoples run into the power of the state," says Bequelin, "but China is unique in the Tibetans lack of ability to resist, so the process of assimilation is much faster."