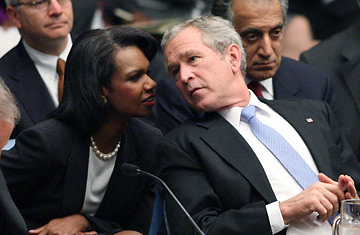

United States President George W. Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice

You could read the Bush Administration's choice of Maryland for next month's Middle East peace conference as a good omen. Jimmy Carter's Camp David talks in 1978 produced the historic peace deal between Israel and Egypt. On the other hand, Bill Clinton's gathering at the presidential retreat in 2000 broke down in failure and triggered Israeli-Palestinian warfare. Little wonder that leaders from the region are approaching the latest Maryland summit — planned for Annapolis this time rather than history-burdened Camp David — with caution and skepticism.

Indeed, key Arab governments are deeply concerned that the Bush Administration will turn the peace conference into a "photo-op," which they believe could backfire against Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and boost his militant rivals in the Islamic Hamas group, leaving the Middle East in a bigger mess. Senior Arab sources in several Middle East capitals tell TIME that they are skeptical about this conference because the Israeli-Palestinian gap remains wide and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, with less than two months to go, does not appear to have laid sufficient groundwork for the meeting's success. "A lot of homework needs to be done, and there's not much time," says an Arab source.

The fear, the sources tell TIME, is that while Rice may see holding the autumn conference as a success in itself, the Arabs believe the U.S. will disregard their demands for a detailed framework and timetable for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. That failure to signal that serious negotiations are at last being relaunched could critically undermine the standing of Arab peace advocates. "If it becomes just a photo-op, then things on the ground will get worse," complains one Arab official. Adds another senior Arab source: "People will see this, at best, as another protracted process, and we'll be back to square one." That source adds, referring to Abbas by his nickname: "Abu Mazen will be hit hard. Hamas will have a heyday, and say, 'We told you so.' We want to avoid that scenario at all costs." Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert apparently prefers a looser conference agenda, one unlikely to commit to fresh negotiations.

Rice says that she hopes the conference will build on understandings that Abbas and Olmert have reached during six rounds of bilateral talks this year and advance the aim of establishing a Palestinian state. She apparently plans to invite several Arab countries, including Saudi Arabia and Syria, to Annapolis. Saudi Arabia chairs the Arab League committee which promotes the 2002 Arab peace initiative; and Syria seeks the return of the occupied Golan Heights from Israel. Syrian President Bashar Assad said last week his country will not attend if the Golan is not discussed. The Saudis are also hesitant, preferring to withhold tacit recognition of Israel until significant progress is made toward a Palestinian state. Jordan and Egypt, which already have peace treaties with Israel, are concerned that failure will benefit the region's Islamic radicals.

The Arab worry, sources say, reflects persistent doubts about how far Bush is really prepared to go — for example, in applying pressure on Israel to make concessions — to broker a historic peace deal. "The record of the administration does not bode well," says an Arab official. "This Administration has not done anything on the Palestinian issue, apart from saying in 2002 that they want a Palestinian state but failing to follow up on that. Getting anything out of them has involved getting it with a big wrench."

The skepticism has been reinforced by Arab perceptions that Olmert will eventually decline to make the politically difficult compromises on core issues like territorial withdrawal, refugees and control over Jerusalem that Palestinians believe are necessary to end the nearly 60-year-old conflict. "The devil is going to be in the detail," says an Arab official. "The gaps are going to be huge." Moreover, in talks with Rice in New York two weeks ago, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud al-Faisal complained that Israel's failure to halt the construction of West Bank settlements raised questions about its good faith going into negotiations. Addressing reporters later, he said that to prove Israel's seriousness about reaching a deal "there should be a moratorium" on settlements as well as construction on Israel's separation wall.

As Arab sources see it, the lack of such an Israeli gesture is one of the signs that Rice has not finished preparing the way for the conference's success. They worry, for example, that Rice has not developed a Plan B if Abbas and Olmert can't agree on a framework and timetable that charts the future of their negotiations. "What if the Palestinians and Israelis do not reach a general framework?" asks an Arab source. "Do the Americans have something ready that they can pull out of their pocket and say, 'These are our suggestions?' And will they be willing, then, to use any kind of encouragement or pressure on Israel to accept certain issues?"

Egyptian Foreign Minister Ahmed Abul-Gheit told an Arabic newspaper recently that in discussions with Arab diplomats Rice had articulated a more encouraging American vision for the peace process. "But I am being perfectly clear here," he added, unless a framework for a peace deal is established first, "this meeting will not meet its goals and will instead reflect negatively on the Palestinian-Israeli future, the future of the entire region, and perhaps even the future of the relationship between the Arab-Islamic world and the Western world." Such dire warnings may be pre-conference jockeying, but perhaps wisdom to take to heart, considering the tumultuous events — the second intifadah — that followed the collapse of peace hopes seven autumns ago in Camp David. Who knows what Annapolis will deliver.