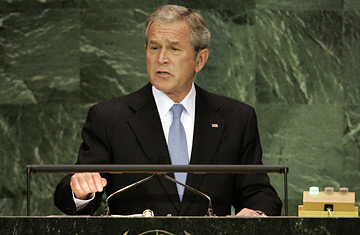

U.S. President Bush addresses the 62nd session of the United Nations General Assembly at U.N. headquarters, September 25, 2007.

For all their nasty fights, maybe George W. Bush and the United Nations were meant for each other. They speak the same wide-eyed language of idealism, setting goals that are heavy on optimism and light on planning. And they love to strike heroic notes in the face of discordant reality. Bush tapped into that romantic synergy at the General Assembly Tuesday, calling on the U.N. and its members to rise to the promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and using that founding U.N. text as a sounding board for a speech on global liberation from tyranny, poverty and disease.

Bush laid out the universal declaration's broadest imperatives, which he said are necessary for true freedom and are central to the U.N.'s larger purpose. "Every member of the United Nations must join in this mission of liberation," he said, ticking through the declaration's list of "rights" to protection from poverty, illiteracy and disease. That's a fairly progressive position: liberal economists, like Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, have said that basic human rights, like the right to vote, are only as good the social and economic rights that allow for them to be exercised effectively. Bush would never endorse the establishment of such broad rights, which tend to be guaranteed only in welfare states, but he is claiming some of those ideals for his own ends.

Maybe Bush is just toying with the U.N.; employing the rhetoric of the left for the policies of the right is something of a signature move for the President. His compassionate conservative agenda famously undercut Democratic claims to superior humanitarianism. Bush has boosted foreign aid throughout his presidency, but has conditioned it on adherence to conservative principles, like those on abortion. In Latin America last spring he spent much of the trip talking about social justice and promoted the idea of Bolivarian revolution, even as he held the line in trade negotiations and on foreign aid.

Bush's social conscience is not just talk, though. Even his fiercest critics give him credit for good-faith pursuit of charitable ends. Most of the Democratic presidential candidates support the faith-based alliances he has built with parochial charities and agree that they have tapped into an important resource for community assistance programs at home and abroad. Foreign aid experts say some of his new foreign aid programs are not just well-funded, they actually work. "He deserves credit for that," says Tim Rieser, the Democrats' top staffer on the Senate committee that oversees foreign aid.

But Bush also has a history of overpledging and underdelivering on some of his high-minded promises. His former faith-based outreach chief, David Kuo, has savaged Bush for not sufficiently funding the programs he promoted. Some of Bush's new, unilateral foreign aid programs have drained funds from older, multilateral ones. "He cuts certain programs to fund others," says Senate aide Rieser. "He just cares about his own initiatives." While proposing to boost funding this year for his overseas disease-fighting program, PEPFAR, for example, Bush suggested cutting funding for the U.N.'s Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria from $750 million to $300 million.

Bush's mixed record on humanitarian follow-through hurts his argument that social and economic rights are needed for true liberation. Worse, the Administration's handling of the Iraq war undermines what credibility remains. The Administration sold the conflict as a war of liberation, and asserted that political liberty alone would be enough to produce prosperity in Iraq. But Bush failed, dramatically and tragically, to plan support for the very social and economic needs he now says are necessary for true liberty.

Bush likes to say that freedom isn't free; in Iraq, he may have learned that it isn't easy either. But it will take more than an idealistic speech at the U.N. to convince observers there and abroad to fall in love with his vision.