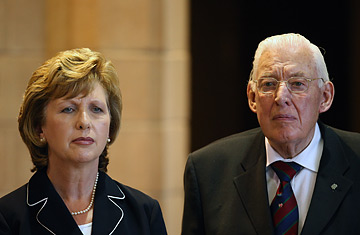

Northern Ireland First Minister Dr. Ian Paisley, right, stands with Irish President Mary McAleese for the first time, at Somme Heritage Center, which honors the sacrifices of British soldiers from Ireland in World War I, at Conlig in Northern Ireland, Monday, Sept. 10, 2007.

The elders of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ireland aren't usually on the streets of Belfast at 2 a.m., an hour more associated with sin than with the business of their church. So, when they emerged from the Martyrs Memorial Church after a five-hour meeting Saturday to make an announcement, the time of day alone was an indication that something unusual was afoot.

The bombshell announcement? Ian Paisley, the First of Minister of Northern Ireland, had suddenly decided to step down as moderator of 12,000-strong Protestant congregation in January, after almost 57 years in charge. Retirement shouldn't be far from Paisley's mind at the age of 81, but the circumstances indicated he may be jumping before being pushed by an unprecedented revolt among his most ardent followers.

The Free Ps, as they are known in Northern Ireland, have for decades been the bedrock of support for Paisley, who founded the fundamentalist church in 1951 and whose leadership ever since has been unquestioned and unchallenged. It was also the network behind the Democratic Unionist Party he founded 20 years later, and which in turn propelled him to the First Minister's office this past May.

It's his new job that's the problem for his flock: Paisley's earthly power is the result of a peace settlement that requires him to share government with Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA, the nationalist movement he has devoted his political career to fighting. Many Free Presbyterians have buried relatives killed by the IRA; others were simply upset by the compromises he made and appalled by photographs of Paisley laughing heartily alongside Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness, a former IRA leader.

Paisley was well aware of the unrest. A delegation of Free Presbyterian ministers had urged him last May to reject the peace deal last May, and some became openly critical when he ignored their advice. Theological warfare ensued: One senior cleric accused Paisley of "abandoning of a truly Biblical position regarding murderers in government." Paisley hit back in a Church newsletter, accusing his critics of "slandering God's leadership" and warning that "it is the ploy of Satan to attack those whom God has signally appointed and specially anointed as leaders in His work."

But the First Minister may have underestimated the depth of opposition among his own base. Paisley's followers had confidently predicted he would be reelected as Free Presbyterian moderator last week, but the strength of feeling at the church meeting changed all that. A deal was crafted that allows Paisley to step down without a vote. In return, critical articles were taken off the Internet by his opponents, although they described his removal as "a start."

The move is a worrying sign that despite Paisley's credentials as the longtime firebrand militant leader of the most uncompromising wing of the pro-British loyalist community, his path of compromise has failed to convince large sections of the Protestant community. Mindful of concerns among his base, Paisley's party has suggested that public contact between him and McGuiness might be scaled back. But the settlement that brought them together remains sound. Paisley has been in politics almost as long as he's been in the pulpit: he ensured that his rivals for the unionist vote were beaten at the ballot box before he took the plunge with Sinn Fein, so his internal critics currently have nowhere to go. Politically, he can afford the loss of his church. The Free Presbyterians, when children are counted, still amount to only a little over 5% of the DUP's vote.

Paisley preached as normal later on the Sunday morning of the church coup, and had put his First Minister's hat back on by Monday afternoon. He talked about making sure their political apparatus represents "all sections of society": practically that means his office funds things like Belfast's growing gay pride festival, even as Paisley the preacher continues to condemn "sodomites." It's a contradiction much of Northern Ireland can live with. In a society plagued by religious division, Ian Paisley may have become the unlikely example of the separation between church and state.