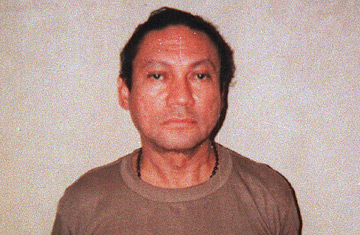

A mug shot of deposed Panamanian General Manuel Antonio Noriega.

Usually old dictators go to Paris to while away their days in opulent exile. But it looks as if Gen. Manuel Noriega of Panama will spend the next decade in a French prison instead of one of the Parisian apartments he bought with drug money in the 1980s. On September 9, Noriega is slated for release from a Miami federal prison, where he spent the past 17 years on drug trafficking charges stemming from the shipment of millions of dollars worth of cocaine from Colombia to the United States. In 1999, he was convicted in absentia on the money laundering charges in France and faces 10 years in prison and a fine of 11 million euros. It remains unclear whether Noriega will appeal the extradition order or go to France and hope for the best.

The U.S. Attorney's Office in Miami successfully met the requirements for extraditing Noriega to France in demonstrating the French had probable cause for charging the deposed general for money laundering. There is also a valid extradition treaty between the U.S. and France. The next step will be for Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to sign off on Noriega's surrender to France.

However, legal scholars maintain that sending Noriega — currently the world's only recognized prisoner of war — to France would violate the terms of the Geneva Convention if Paris fails to accord him POW status. Despite assertions from the U.S. Attorney's Office in Miami that the French government intends to honor the Geneva Convention, Noriega's Miami-based lawyer Frank Rubino maintains that may not be the case. "The French Ambassador to Panama — Pierre-Henri Guinard — publicly stated Gen. Noriega will not be treated as a prisoner of war but as a common criminal," Rubino told U.S. Magistrate William Turnoff during an extradition hearing on August 28.

Whether the French call Noriega a POW is more than academic, says Detlev Vagts, who teaches international law at Harvard. "You have to refrain from transferring a POW to a country that you think won't treat him as a POW," Vagts told TIME. "We returned a lot of German POWs to the French at the end of World War II. There are plausible charges that the French did not treat them as they should — kept them a long time and caused them to do dangerous work in mining."

"There is a principle here that certainly transcends Noriega and that's strict interpretation of the Geneva Convention," says Jon May, Noriega's Fort Lauderdale-based attorney. "Strict interpretation protects our soldiers around the world... In [The Black Hawk Down incident] in Somalia we went to warlords and said we expect you to respect the Geneva Convention. During the first Desert Storm issues of the Geneva Convention came up all the time. There may be no sympathy for Gen. Noriega, but that doesn't mean we don't respect his rights."

But France isn't the only country that wants Noriega. Panama wants him for the far more serious crimes of murder and human rights violations. "We requested extradition," says Frederico Humbert, the Panamanian ambassador to the U.S. "We insisted on it. If the U.S. court system decides he goes to France, he will then have to go to Panama to fulfill the time that he needs to pay for the crimes that he has been found guilty of in our courts." Over the years, the Panamanian government has made several extradition requests, the latest as recent as January.

Rubino says that Noriega, too, wants to go home to Panama. He says the former strongman, who now walks with a stoop and is 73 (or 69 according to the birth date cited by Assistant U.S. Attorney Pat Sullivan in court documents), wants to spend his final days with his grandchildren as an "elder statesman." Rubino wonders why his client can't just go home to face the music. "He committed the heinous crime of purchasing an apartment in Paris," Rubino, says in a mocking tone. "That's more important than murder and kidnapping?" Noriega's POW status would end if he sets foot on Panamanian soil and he signs a release provided by the International Committee of the Red Cross, says Vagts. But, as federal prosecutor Sullivan noted, if Noriega first went to Panama, it's unlikely he would ever set foot in France due to "Panama's constitutional prohibition on the extradition of its nationals."

Vagts says that if Paris wants him so badly, they should keep his POW status in order to help the U.S. honor the convention. "Regardless of what France calls him," says Vagts, "under the Geneva Convention, we are responsible to take POWs home. If I were the French, to avoid difficulty, I would let the Red Cross visit him and if he wants to sit in [a French] cell in his Panamanian uniform, I'd let him." The option of wearing his khaki uniform with the stars on the epaulets is but one of the privileges afforded Noriega as a prisoner of war. At present, Noriega resides in a special cell in the Federal Correctional Institute in Miami. His POW status affords him customized living quarters that resemble a condo more than a prison cell, what with its exercise machines, telephone and color TV. If he were treated as a common criminal, says attorney May, "He could be put with violent criminals, where he could be subjected to harsher humiliating treatment, where he could not receive the kind of exercise and fresh air and light that he is entitled to in the U.S." There may be some justice in that. Just not the kind provided by the Geneva Convention.