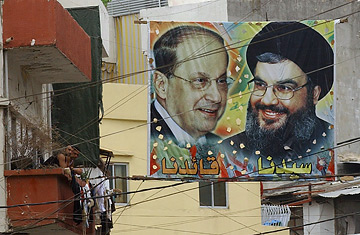

Poster of Christian Maronite leader General Michel Aoun (L), and leader of Hezbollah sheikh Hassan Nasrallah (R), in Beirut, Lebanon, 05 August 2007.

Sunday's Lebanese parliamentary by-election was planned to strengthen the country's U.S.-backed government against the ongoing campaign by opposition forces allied with Iran and Syria to bring it down. But once the votes were counted, the election appears to have strengthened the hand of the opposition and highlighted the weakness of the current power arrangement in an increasingly divided country.

The election was held to replace two assassinated legislators from the anti-Syrian ruling coalition of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora. And the government comfortably won one of those seats — the one formerly occupied by the late Walid Eido, a Sunni member of parliament who was killed in June by a bomb set next to his favorite beach club. But holding Eido's seat wasn't much of a challenge: He had represented a strong Sunni Muslim district in West Beirut where support for Siniora is strong. The bombshell came in the majority Christian district known as the Metn in the mountains just north of Beirut: There, former President Amin Gemayel, one of the stalwarts of the anti-Syrian coalition, lost to a small-time opposition candidate, Camille Khoury, who is unrecognizable to most Lebanese. Though Gemayel was defeated by just 418 votes, the loss is all the more stunning because he was campaigning to fill the seat once held by his son, Pierre Gemayel, who was gunned down in the suburbs of Beirut in November.

Khoury's victory is a reflection of the popularity of his patron, Michel Aoun, a charismatic and enigmatic former general who heads the country's largest Christian political party, the Free Patriotic Movement. Aoun's popularity confounds any attempt to read Lebanon as a battlefield in a "clash of civilizations," because he and his party are openly allied with Hizballah, the Iran-backed Shi'ite Muslim political party and anti-Israeli militia that leads the opposition.

What could Lebanese Christians possibly have in common with Hizballah, the Islamist resistance movement? Perhaps it is the fact that Aoun's Christian supporters and Hizballah's rank and file are motivated by a shared animus towards Lebanon's political elite, a handful of families such as the Gemayel, whose progeny resurface in government after government. In fact, many of the supporters of the current government are civil war-era militia leaders, who accommodated themselves rather nicely to the years of Syrian occupation, but who have now emerged wearing business suits and talking U.S.-friendly language about democracy and independence.

Of course, neither Aoun nor Hizballah is a poster child for democratic civil society. Aoun, as head of the Lebanese army in the early 1990s, launched a series of disastrous civil conflicts, while Hizballah sparked a pointless war with Israel last summer that resulted in the deaths of almost 2,000 Lebanese, many of them children. Still, both popular movements tap into the general resentment of average people who have watched as a relatively small number of Lebanese — well represented in the anti-Syria ruling coalition — have cashed in on the post civil-war reconstruction of the country.

The latest election results and the wider campaign against the government reflects not so much an attack on democracy as it does the failure of the country's sectarian system to resolve internal disputes. The system, which reserves the presidency for the Maronite Christians, the Prime Minister's job for a Sunni, the speaker of parliament for a Shi'ite and generally distributes power on the basis of ethnicity and sect, was originally created to achieve stability through a careful balance of power. Instead, it has produced political deadlock and a system dominated by leaders whose domestic power is based on alliances with foreign powers.

Yes, Lebanon is a battlefield, but not in some global religious-ideological war. Instead, its politics reflects an old-fashioned power struggle between the fading regional superpower — the United States — and the rising power of Iran and its Syrian ally. And that's a conflict that is not going to be settled by any Lebanese by-election.