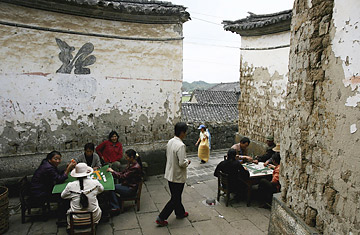

Villagers play mah-jong in Heshun, Yunnan Province, China.

When interviewing a Chinese source about a sensitive subject, I sometimes try to put them at ease by first chatting about a) their favorite food; b) China's breakneck-speed economic growth; or, best of all, c) their pride that Beijing will host the 2008 Summer Olympics. Once the interviewee has expounded on a particular kind of tofu, or their son who's now studying international trade, or the prowess of China's table-tennis team, I segue to the real topic at hand. The strategy works surprisingly well.

Imagine my surprise, then, when option C (the Beijing Olympics) bombed in the southwestern province of Yunnan. Thousands of kilometers away from Beijing, Yunnan is home to members of nearly half of China's 56 ethnic groups. Culturally, many of the province's citizens have more in common with their Burmese and Laotian neighbors than they do with the Han majority that makes up most of China. Indeed, the Chinese proverb "The mountains are high, and the emperor is far away" seems tailor-made for the people of Yunnan.

Despite China's size and heterogeneity, it's easy to buy into the myth of a monolithic state. That myth is burnished by central government in Beijing, and also by the common habit among its citizens of starting a sentence with the phrase, "We Chinese..." Every citizen knows that their glorious homeland boasts 5,000 years of history — a fact that regularly gets repeated when a reporter from a mere pup of a nation 231 years old gets too uppity.

Nevertheless, China is nowhere near as unified as foreigners — or even "we Chinese" — assume. Narrowly, this means that the people of Yunnan have little interest in a certain sporting event that will commence on August 8, 2008. One Yunnan truck driver, when asked about the Olympics, just shook his head in disgust. "So much money is being wasted," he said, the first time I'd heard someone in China refer so negatively to the Summer Games. "It's not going to make my life any better. Why should I care?"

On a broader level, though, the Olympic apathy in Yunnan points to a more troubling trend of rising regionalism at the expense of central-government authority. The Chinese know their history well: Beset by warlords, the Middle Kingdom suffered a multitude of fractious eras, including a brutal multi-century stretch known as the Warring States Period.

Today's fissures in central authority might seem tiny by comparison, but they are significant nonetheless. In the boomtowns of Shanghai and Guangzhou, municipal meetings are often conducted in local dialects, as opposed to the national language, Mandarin. Trade rivalries between provinces have resulted in absurd internal tariffs that foreign manufacturers must pay when transporting their products out of China. And even though Beijing executed the country's former top food and drug regulator for graft last week, the international scandal over tainted Chinese products speaks more to the central government's inability to monitor what's going on in factories nationwide than of simple malfeasance by a few renegade Beijing officials. In many places, regional strongmen exert more power than President Hu Jintao.

I wasn't thinking about any of that when I mistakenly tried to ingratiate myself in Yunnan by bringing up the Olympics. But it did make me sympathetic to a dejected vendor sitting idly by her stall as nearby competitors did brisk business selling ethnic-themed tourist trinkets. Her wares? Olympic key chains and stuffed toys modeled after the Beijing 2008 mascot. "No business today," she sighed. "Maybe tomorrow."