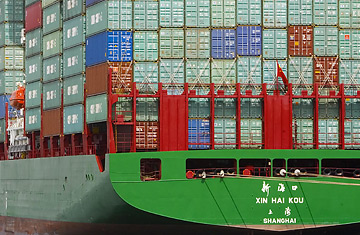

Containerized cargo is stacked high on a China Shipping Line freighter.

As first conceived, the twice-yearly Strategic Economic Dialogue meetings between the U.S. and China were meant to be high-minded affairs, where long-term, structural issues of interest to both countries would be thoughtfully discussed. But no matter how much U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Chinese Vice Premier Wu Yi try to cast this week's summit as an intellectual exercise, the main issue confronting them is by no means academic. China's trade surplus with the rest of the world is now at a projected $400 billion, and there is no sign that it is going to shrink anytime soon. The surplus this year will be well above 10 percent of China's total economy, a level more typical of a small Persian Gulf oil exporter than the third largest trading nation in the world.

The global trading system has a built-in mechanism, of course, to deal with a country whose trade accounts get seriously out of whack with the rest of the world: currencies adjust in value against each other. China, with its surpluses, should see the renminbi go up over time, while the U.S. (with its enormous deficits) should see the dollar decline. But China has defied this system by clinging to a more or less fixed exchange rate. It has, after all, served the country well: the cheap RMB has encouraged the development of China's export-led industries, and attracted foreign capital to build factories. As long as the currency is vastly undervalued against the dollar and the Euro — and few economists believe it's not — that will continue, only increasing the trade surplus.

There is little sign that things will change. On May 18, in advance of the talks in Washington, China announced a token increase in the range in which it will allow the RMB to trade against the dollar. Beijing also raised interest rates and increased the amount of capital banks need to keep in reserve — both moves intended to slow China's breakneck economy. On Monday, Beijing also announced it was taking a 10 percent stake in the Blackstone Group, the big U.S. private equity firm that is about to go public on the New York Stock exchange, indicating that Beijing would like to earn a slightly better return on at least some of its $1.2 trillion (and climbing) in foreign exchange reserves. But at $3 billion, the Blackstone investment is really just a drop in the bucket, while the economy-slowing moves on Friday may on balance serve to increase China's ongoing trade deficit by depressing its appetite for imports. Taken together, they signal Beijing's conviction that only ever-so-slow changes to the status quo are acceptable.

By contrast, many economists believe the only mechanism to address the global trade imbalance is a large, one-off currency revaluation in Beijing, increasing the value of the RMB significantly and enduring the domestic economic pain this would cause. More than anything, this would show the world Beijing is serious about being a responsible player in the global trading system. It would also help defuse the mounting antagonism in Washington and other foreign capitals over the trade issue.

This is critical. So far, the trade relationship with China has been a minor issue on the political landscape, largely because U.S. unemployment is very low. But the economy is slowing, and an election year looms. If the U.S. economy stumbles, China will be the biggest, fattest target on which to pin the blame. Meanwhile, China will likely continue recycling its massive foreign reserves, possibly making itself an even bigger target by going on a buying spree similar to Japan's in the late 1980s and early '90s: Japan buys Hollywood! Japan buys Pebble Beach! Japan buys Rockefeller Center! Remember too, Japan was an ally; the idea of a traditionally antagonistic (and, nominally, Communist) nation buying up U.S. assets won't likely sit well with American voters. Already one major acquisition — the attempted 2005 takeover of U.S. energy firm UNOCAL by a Chinese oil company — was nixed following political outcry. What will China try to snap up next?

For the time being, at least, Beijing will continue to be a buyer of U.S. Treasury debt, helping keep interest rates low and the U.S. economy out of recession. But Paulson must know that the current trade relationship with China is seriously out of whack, and that something needs to give on the currency front sooner rather than later. He will no doubt try his best to persuade China that it is in its own interest to move faster — much faster — on the currency front this week. Whether China will listen is another matter.