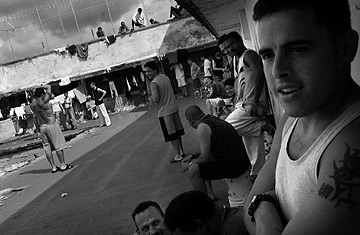

The male section of the Los Teques Prison

(2 of 2)

On arriving at Los Teques, the American was handed a broken slab of rubber and sent to a corner spot on a concrete floor. That was to be his living quarters. Basic articles like toilet paper, soap and razors were not provided. There was no toilet or shower and he bathed by throwing cold water over his head. Health services were geared mostly toward treating stab and gunshot wounds, he said, unsure why he and his companions had boils forming on their skin.

To improve his situation, the American paid a bribe — which embassy officials say is usually around $1,000 — for a spot in a special upstairs area where living conditions are more tolerable. There, inmates can have access, for a price, even to such luxuries as Direct TV or an Xbox. Some install kitchens in their rooms and pay someone to bring food from outside, so as to avoid the sardines and third-grade meat served in the prison. Funds come from prisoners' families and, in some cases, taxpayers' money in their home countries.

Still, even the luxury section is at double capacity. In fact, the American says, he is envious of the prisons depicted in the Hollywood movies he watches there. Just inside the second gate, where many of the shootings allegedly occur, inmates mill about freely in the hallways, far from their cells, joking around and chatting on cell phones, which are supposedly not permitted.

"The director tells us to be careful of this area or that — because that's where the guns and drugs are," said a consular official at an embassy in Caracas, asking to remain anonymous for fear of jeopardizing efforts to repatriate prisoners. Indeed, with no visiting rooms and few guards in sight, visitors must give inmates a small tip to fetch the prisoner they've come to see. Forget uniforms; prisoners wear the street clothes of their choice, though they are not supposed to wear dark colors that can hide blood spots. When inmates' girlfriends come to visit, they go straight to the cells, which they are free to use as a love shack.

The women's jail is more pleasant, with an open-air courtyard and views of surrounding hills. But inmates there say only eight guards watch over some 270 prisoners, and they don't have pepper spray or handcuffs. "It's not the good Venezuelans that are here; it's the thugs," said one foreign inmate there. "If they decided to take over the place, they could."

Many of the foreign inmates are awaiting repatriation to their home countries, under bilateral prison transfer agreements. But their departure requires the necessary paperwork to be completed by the notoriously slow Venezuelan bureaucracy. "Obviously if you've got people being killed all the time, you want the prison transfer agreement to work," a consular official at one embassy said.

Officials at three Western embassies in Caracas say Interior Minister Pedro Carreno has not signed a single transfer document for their nationals since President Hugo Chavez appointed him in January — and they're getting antsy. They said that at a recent meeting with ministry officials, representatives from every major embassy grumbled that they were in the same predicament The ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

"It's rough," said one male inmate awaiting transfer. "Like a jungle."