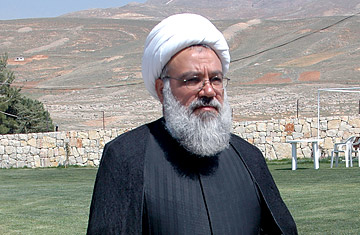

Sheikh Sobhi Toufeili, a founder of Lebanon's militant Shi'ite Hizballah and the group's first secretary-general, April 21, 2007.

Twenty years on, Toufeili has evolved into one of the most outspoken — and unlikeliest — critics of Hizballah and its sponsors in Tehran, accusing both of corruption and of selling out the ideals of Iran's 1979 Islamic revolution. "Hizballah is no longer a real liberation force but just a tool for Iranian interests. Hizballah has become a very bad and corrupt organization," he said in an interview with TIME.

Such views have little traction in the Shi'ite villages of the eastern Bekaa Valley where Toufeili lives. Local residents openly mock the stubborn cleric, accusing him of being on the payroll of Hizballah's opponents. Small wonder, then, that he rarely leaves his home, and that his bodyguard rarely leaves his side.

Toufeili wears the Shi'ite clerical garb of white turban and black full-length robe, and sports a thick white beard. His tiny black eyes, glinting like chips of anthracite, are almost hidden in the fleshy folds of his chubby, tanned face. A man of cast-iron principles, Toufeili is a product of the eastern Bekaa, an area notorious for its lawlessness, its feuding Shi'ite clans, smuggling and narcotics production. When Israel invaded Lebanon in June 1982, Toufeili was in Tehran and helped organize the deployment in Lebanon of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards who recruited and trained hundreds of young local Shi'ites to fight Israel's occupation, thus creating the nucleus of Hizballah.

He led the organization during the period of spectacular suicide bomb attacks against Western targets and the kidnappings of foreign nationals in the 1980s. Among those attacks was the suicide truck bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in October 1983 which killed 241 American servicemen. At that time, Hizballah had yet to publicly declare its existence and goals, and its leaders have always denied involvement in the anti-Western actions. But Toufeili admits that the group was responsible for the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks.

"The Marines were not civilians. I considered the Americans as an occupying force and I fought them," he says in his soft, gravelly baritone. While he remains "proud" of the attack, he says that he was not personally involved in the operation. "If I had had anything to do with it I would say so because my relations with the Americans are not so good," he says with a soft chuckle. Toufeili is classified by the U.S. Treasury Department as a Specially Designated Terrorist, one of six Lebanese Shi'ites included on the list.

While willing to fess up to the bombings, Toufeili insists that the kidnappings of Westerners "had nothing to with Hizballah. Nothing at all." Indeed, as he puts it, Iran's policy of using Lebanese Shi'ites to kidnap Westerners was a "mistake" which he tried to redress.

"The hostage situation ruined the image of the resistance [against Israel] and the image of Islam," he says. The stern, no-nonsense cleric is not given to naming names and recounting anecdotes. He keeps his many secrets to himself. But he did offer one intriguing episode from the hostage-taking era. In early 1986, Toufeili says he was in regular telephone contact with the Lebanese kidnappers, urging them to release their captives. In May of that year he says he extracted a pledge that all the hostages would be released within a week. A day later, he was visited by the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, who bore a message from then Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. Assad wanted the hostages released. Could Toufeili help? The Hizballah leader reassured the Syrians that the issue would be resolved shortly.

But the arrangement collapsed, Toufeili says, when, just three days after securing the promise from the kidnappers, Robert McFarlane, the former National Security Advisor to President Reagan, made his now infamous secret trip to Tehran, accompanied by Colonel Oliver North, as part of the arms-for-hostages dealings.

"We discovered then that the hostages were a big treasure for Iran. They wanted to sell the hostages piece by piece," Toufeili says. The story is impossible to verify. To this day, the identity of the kidnappers remains unknown and Toufeili says he has no intention of breaking his silence.

Toufeili's unbending nature placed him at odds with the younger and more pragmatic generation of Hizballah officials who gained prominence at the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990. And he crossed swords with the Lebanese government in 1997 when he launched a campaign of civil disobedience to protest official neglect of the impoverished Bekaa. Toufeili insists he does not dwell on the past, and spends most of his time studying weighty tracts on Islamic jurisprudence. Yet one cannot help wondering what dark secrets swirl in his memory when he gazes out of his window at the imposing walls of the Sheikh Abdullah barracks down the road.