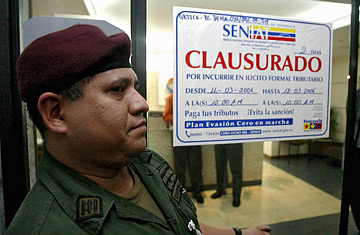

A policeman stands guard in front of the French oil company Total, after it was closed down by Venezuela's tax authority.

But Seniat's success is also politically charged. The funds it collects pay for development programs at the heart of Chavez's socialist project, describing its work as proof "that the model of Socialism of the 21st century is being executed for the Bolivarian people." When the Shell oil corporation agreed last month to pay some $13 million for income tax irregularities, Seniat hailed the event as a landmark triumph for its "revolutionary process to rescue full tax and oil sovereignty."

While such rhetorical excesses may be unusual for a tax agency, its revolutionary tenor could be an attempt to play to the gallery of Venezuela's poor. But Seniat's hard-line approach to filling state coffers has taken some getting used to for Venezuelans rich and poor. They are growing accustomed to seeing neighborhood stores and cafes barred by thick Seniat tape and signs declaring closure for 48 hours. Seniat press releases announce new temporary closures almost daily, targeting everything from health clubs to the Hard Rock Caf for irregularities in income tax, value-added tax or other payments. In a February statement, the agency patted itself on the back for shutting nearly 4,000 businesses in only eight weeks.

Seniat is not afraid to get tough with the big corporations, either. The government has used hefty retroactive tax bills as leverage in contract negotiations with international oil firms. It refused to finalize new contracts until such companies had settled their tax bills. Seniat also closed ExxonMobil's Caracas headquarters for an alleged value-added tax violation in the midst of high-stakes negotiations in which the government is seeking more control over multibillion-dollar oil projects. And the tax authority's chief, Jose Vielma Mora, adopts a nationalist tone not unlike that of his president, once accusing a U.S. oil company of failing to comply with tax law because it saw Venezuelans as "natives in loincloths."

The government itself, however, may not be the model of accounting transparency suggested by the moralizing tone of its tax crusade. A National Assembly anti-corruption commission began its work in January with 700 cases of alleged corruption to sort through, including accusations against the bank-deposit protection fund and a state agricultural development fund. An embezzlement scheme at a sugar-processing plant in Chavez's home town of Barinas was also exposed. And, just this week, lawmakers accused public officials of donning a revolutionary faade for personal and financial gain.

Still, there's no doubting Seniat's success in nudging Venezuelans to pay up: By this year's end-of-March tax day, the government had collected nearly three times as much in non-oil income taxes (measured as a percentage of GDP) as it had during the 1990s, according to Seniat. "The tax culture has changed," says economist Tamara Herrera of Latin Source, an economic research firm. That might be because Seniat's aggressive tactics have companies terrified to try any tricks. In a region long chided by the U.S. for allowing mass tax-evasion, many see Venezuela's government as proving a model of good governance as far as collecting tax revenues goes. But collecting taxes to fund a self-styled socialist revolution may not be quite what Washington had in mind.