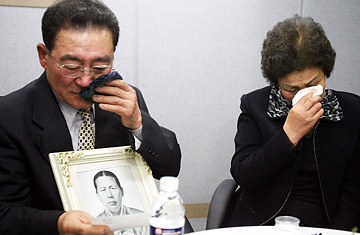

South Korean Kim Yong-hun, 71, left, and a family member wipe their tears as they talk to their North Korean relatives through a screen during a video family reunion session at the video conferencing room of Red Cross in Daejeon, south of Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, March 27, 2007.

Byun rises from his seat when the video feed begins and when his half sister and nephew suddenly appear on the screen. He introduces his side of the family, who take deep bows, then reaches to his left for the photo of his recently departed 88-year-old father. "Our father died only ten days ago," he says, holding up the frame in front a camera perched on top of the screen. "When he learned he was finally going to meet you, his heart and mind couldn't handle the excitement." Fighting back tears, his half sister dabs her eyes with a white handkerchief while her nephew's eyes redden after hearing the heart-rending news. For the next two hours, the Byun clan hold up photos to each other, chat about the family tree and promise to work toward unification so they can meet again.

But this could probably be the last time Byun will see his relatives in the North. Tens of thousands of other South Koreans are still on a waiting list for both video and face-to-face exchanges. "It will take at least ten years for everyone to see their relatives at this rate," predicts Young Woon Choi, head of the Inter-Korean Cooperation Team. The video exchanges cost the Korean Red Cross $340,000 a pop and can be canceled at a moment's notice or whenever the North decides to throw another hissy fit. Not surprisingly, many folks are on tenterhooks, waiting to hear if theyve been selected.

Other family encounters don't go off without a hitch. "Why did you leave my mother in the North when you went to the South?" a young North Korean man asks his obviously frail 93-year-old South Korean grandmother. His antipathy resonates, and the distressed woman's head drops. A minute later, a Red Cross doctor enters the room with a portable bed. But the rest of the family does not let the distraction gobble up precious time, and one of the siblings quickly sheds light on the subject, explaining her mother tried to return but couldnt because of the war.

In an identically furnished room down the corridor sits another South Korean family, listening to a female North Korean relative, wax lyrical about "Great Kim Jong Il" and how his philanthropic nature enabled them to lead a good life. Her South Korean relatives are not impressed, and implore their relative to stop "talking politics" and stay on topic, in other words, talk only about kin.

Of course, God and country, are taboo topics during these mostly tear-filled reunions, but almost all the North Korean families praise Kim Jong Il at least several times during the two-hour live broadcast. "All our education is free and we don't pay for hospital care," says a sixty-something North Korean woman, who is sitting on a long purple sofa with her sister and father in a room that also doesn't seem too conducive to reconnecting with relatives one hasn't seen in more than a half century.

Her South Korean relatives nod knowingly.