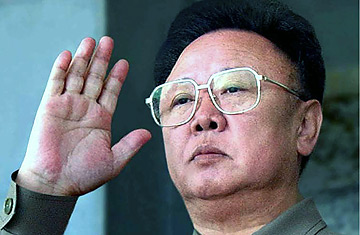

North Korean leader Kim Jong Il reviews a military parade in Pyongyang, October 10, 2005.

But at the end of today's session, North Korea said it was willing to take the initial steps toward dismantling its nuclear arsenal — at least in principle. Lead U.S. negotiator Christopher Hill said, "We hope we can achieve some kind of joint statement here."

Last month, Hill met in Berlin with his North Korean counterpart, Kim Kye Gwan, and the first signs of a possible thaw became apparent. Hill referred to "good signs" after the meeting, and now diplomats say they hope that at the current round of talks Pyongyang will agree to shut down its nuclear reactor at Yongbyon, which produces the basic fissile material it needs for the bomb. There is also talk that international inspectors may be allowed back into North Korea to visit Yongbyon and perhaps other nuclear sites. In return, the U.S. and its allies in the talks — China, Russia, Japan and South Korea — would move to provide significant energy assistance to impoverished North Korea. Washington and Tokyo would also begin steps to normalize relations with the North.

Optimists who believe the talks may actually get somewhere this time say the basic tension underlying the Bush Administration's stance toward North Korea — does it want a nuclear deal with Pyongyang or does it seek to punish it via isolation and sanctions — has been resolved. As a senior Administration official told TIME in mid December, "Our clear priority is reaching an agreement for the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula."

The presumption, then, is that U.S. engineered financial sanctions that have so irritated Pyongyang will be dealt away as part of a grand compromise. The U.S. clearly struck a nerve when in September 2005 the Treasury Department pressured a Macao bank, Banco Delta Asia, to freeze North Korean accounts held there. (Treasury accomplished this mainly by getting major banks in the U.S. to shut down their correspondent accounts with Banco Delta Asia, effectively isolating it from the international financial system). The U.S. has said it suspects the North uses the accounts to launder money gained through counterfeiting U.S. currency and narcotics sales. South Korean sources have also told TIME that some the accounts held at the bank are controlled by elites in Pyongyang ("people Kim Jong Il has to deal with every day," says one intelligence source) who were infuriated by the freeze.

Will the sanctions, in fact, be dealt away if Pyongyang agrees to shut down Yongbyon and take other steps to stand down its nukes? Ultimately that's President Bush's decision, and he was recently asked point blank whether whether the U.S. was going to lift them. His response (to an interviewer from the Wall Street Journal editorial page): "They've got to give up their weapons program."

In that response, some see the outlines of a deal. If the North commits to specific actions eliminating its nuclear program — and then actually takes them — the sanctions come off. The tough part is that the North doesn't want to be seen succumbing to U.S. pressure. A deal would thus require negotiating language and action that would (1) allow Pyongyang to save face as it gives up a valued program and (2) permit Washington to claim a breakthrough without looking like it's rewarded a rogue nation. Oh, and (1) and (2) have to happen just about simultaneously.

Nevertheless, Hill said he expected a draft agreement by tomorrow that would lay out the steps that needed to be taken and a time frame for all the choreography to occur (Hill hoped everything could be accomplished in "single-digit weeks.") For the moment, the atmospherics are good — a rare occasion. But don't be surprised as details once again get in the way of a deal. It's happened before.