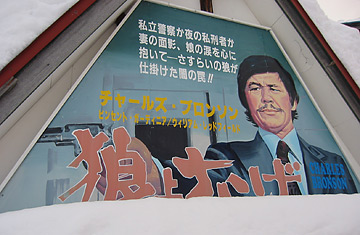

A poster advertising a Charles Bronson movie in Yubari, Japan

Like exhausted mining towns the world over, Yubari faced extinction, but during the 1980s and '90s, city officials tried to arrest its economic decline by borrowing hundreds of millions of dollars — with generous help from the central government — to build massive tourist facilities such as the melon museum, the robot museum and the ski resort. The plan worked for a while, and the city even became known for a winter film festival that attracted stars like Quentin Tarantino (who named a character in Kill Bill after the town). But tourism never paid off, and debts piled up. The city was finally forced to declare bankruptcy last summer. Today Yubari, a frozen city of 13,000 people, is over $500 million in debt.

Sasaya — who sells specialty salt over the Internet — decided it was time to move back. "I wanted to do everything I can to help my hometown," he says. And despite Yubari's woes, Sasaya looks for the silver lining: "One thing I think we can be proud of is that no one has committed suicide."

Yubari is a very Japanese story: Since the postwar era, Tokyo has channeled massive subsidies to its underperforming hinterland. That formula secured the government reliable votes, but it also enabled rural people to enjoy higher income levels, sparing Japan from the social inequality that has beset such rapidly growing neighbors as China. But the policy was sustainable only as long as Tokyo had budget surpluses to burn. Today, Japan may be the world's second-richest nation, but its public debt that is more than 1.5 times the size of its GDP, the highest in the developed world. So, a budget-conscious central government has cut subsidies, and Yubari will have to pay back $293 million over the next 18 years.

The trouble is, as Yubari officials bluntly admit, the money simply isn't there. Since the mines closed, the city's single biggest employer has been the municipal government, and half of its 300 workers will soon be leaving or facing salary cuts of up to 70%. The film festival has been cancelled, and the city-run tourism facilities have closed until they can be purchased by private companies that would consider a coal history museum in a depressed and snowbound mountain town to be a winning investment. (Interested parties can contact Keiji Hosokawa, who runs tourism promotion for Yubari — at least until his department is eliminated in March.) Even as it raises taxes, the city is closing schools, libraries and nursing homes in a desperate effort to cut costs. Unsurprisingly, many Yubarians are simply leaving town. "We'll be forced to provide the bare minimum social services, while having the highest tax burden that is allowed by law," says Hisashi Hirano, a municipal official. "I worry about Yubari disappearing." Hirano, by the way, is in charge of Yubari's public relations.

Of more concern for Japan is the sense that Yubari may provide a glimpse of the future — 41% of Yubarians are older than 65, mirroring Japan's own rapid graying. The city's population is shrinking, as is Japan's as a whole. And, thanks to its massive debt, Yubarians will pay more for less — as may all Japanese if the aging country can't reverse the trend of shrinking incomes and shrinking hope.

Japan's postwar boom lasted decades, and even during the stalled 1990s, it was able to live off the fat. Yubari underscores the reason that Japan's faith in a more prosperous future has been shaken. "Yubari citizens are filled with anxiety about the future, and so are a lot of Japanese people," says Sasaya, the snow piling outside his small shop in Yubari's shuttered downtown. "It makes me wonder where Japan is headed." The answer could lie in another Newtonian law: what goes up, must come down.

— With reporting by Toko Sekiguchi/Yubari