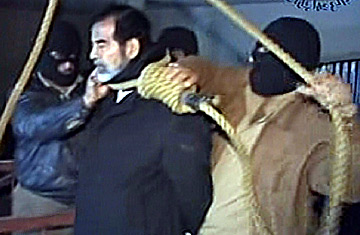

Al Iraqiya television shows masked executioners tightening the noose around former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein's neck moments before his hanging in Baghdad December 30, 2006.

The next time I met Abu Mohammed, in the summer of 2004, he had come to Baghdad with a group of tribal sheikhs to seek patronage from the new Iraqi government. It was a few days after Saddam had been brought to court for the first time, and Iraqis were still absorbing the prospect that justice would be done upon their former tormentor. When I asked Abu Mohammed if Saddam was still in his head, he told me a story about one of his sons, who had a leg blown off by a landmine during Saddam's first folly, the eight-year war with Iran. "For years, he would wake up in the morning and fall out of his bed because he thought he still had the leg," Abu Mohammed said. Saddam had become a ghost limb for Iraqis, he added. "He isn't in my head, but sometimes I think I can feel him."

But it took Iraqis a remarkably short time to get the tyrant out of their psyche. One reason was that there were so many new terrors with which to contend — roadside bombs, suicide bombers, kidnappings and, eventually, sectarian slaughter. The other reason was the televised trial of Saddam, which served as a form of group therapy, on a national scale. As they watched him in court, day after day, Iraqis grew less fearful of him. His frequent outbursts began to seem like schoolboy petulance, and when he was scolded by the judge it was as if the class bully was being sent to the corner by the headmaster. The trial reduced Saddam from an ogre to a mere mortal, then to a figure of fun and finally into a pathetic, shriveled-up old man.

But outside the courtroom, as Iraq went from chaos to a bloody civil war, I would occasionally hear an Iraqi hark nostalgically back to the Saddam era, pointing out that for all the dictator's faults he was at least able to keep his country's sectarian demons in check. As the violence worsened, some argued that the only way to exorcize those demons would be to ditch the democratic process and hand the country back to a Saddam-style strongman. But nobody seriously suggested that Saddam himself be sprung from jail and restored to power. He had become too emasculated to become an ogre again. And without a capacity to cow his people, he could never again control them.

Even the remnants of his old regime, which had morphed into the Sunni insurgency, seemed to lose their fervor for Saddam. Some Ba'athist groups kept up the charade that they were fighting to restore the dictator to his palace, but others quickly stopped referring to him at all and instead recast themselves as "the nationalist resistance" or as "mujahedin," or holy warriors. Many threw in their lot with the new ogre on the scene, Al-Qaeda's Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

After Saddam's appeal failed, remnants of his Ba'ath Party threatened dire reprisals if the government carried out the death sentence. But such threats had been made throughout the trial, and they have amounted to nothing substantial. Most of the violence in Iraq is now perpetrated by people with no love for the dictator. Even if the Ba'athists were to step up their attacks, there's a good chance they would be lost in the general carnage wrought by Jihadi groups and Shi'ite militias.

By last fall, even the insurgents notionally fighting in his name were beginning to wonder if he might not be more useful as a martyr than as the lead actor in a TV farce. One afternoon last October, I watched the televised Saddam trial in the company of Abu Hamza, a field commander of Jaish al-Islami. Iraq's largest insurgent group, Jaish al-Islami is made up mainly of Ba'athists and soldiers from Saddam's army. Abu Hamza had been an officer in Saddam's elite Republican Guard; in previous meetings, he had spoken reverentially about the dictator, describing him as a man who exuded power and gravitas. One description stood out in my mind. "Saddam embodies Iraq's dignity and pride," Abu Hamza told me in the summer of 2005. "When the Americans put him in jail, they locked up our pride and our dignity." Longer than most loyalists, he clung to the hope that "my president" would make a miraculous comeback.

Now, watching his former boss sitting sullenly in the dock, Abu Hamza shook his head sorrowfully. Even a loyal follower could see no pride or dignity there. For the first time, Abu Hamza conceded that his president would never return to power. Then, in a cool, matter-of-fact tone, he broke the final taboo and began to talk of Saddam's death. We spoke of how it might happen: he was sure that the Iraqi government would ignore Saddam's request that he be executed like a soldier, by firing squad. "They will just hang him one night and announce it the next day," he said. "Then they will bury him quietly, and forbid his family from building a proper mausoleum. After that, they will try to make Iraqis believe Saddam never existed."

But Abu Hamza was convinced that the exact opposite would happen. In death, Saddam would achieve immortal martyrdom, and be restored to his rightful place as the dominant figure in the national consciousness. "When they hang Saddam, they will make him once again powerful," he said. He pointed to a TV set. "He will go from there," he said, then tapped on his temple, "to here."