Was it all just a dream?" Michael Moore poses that question at the start of Fahrenheit 9/11, his docu-tragicomedy about the Bush Administration's actions before and after Sept. 11, 2001. Moore's tone isn't wistful; it's angry. He's steamed about the Florida vote wrangle of 2000, the Supreme Court decision to declare George W. Bush President of the United States, the policies of Bush's advisers and especially what he sees as the deflection of a quick, vigorous search-and-destroy mission against Osama bin Laden into an open-ended war on terrorism--"You can't declare war on a noun," Moore said last week--that spawned a dubious and costly invasion of Iraq.

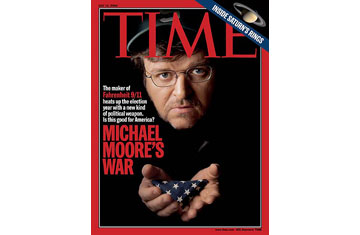

Now, after a week in which his film became the highest grossing documentary of all time--and more than that, a nationwide rally point for Bush opponents, a red flag for Bush supporters, a cinematic teach-in for the undecided and a potential factor in the '04 presidential race--Moore may well be asking, "Is this all a dream?" For starters, is this the same film that not long ago was an orphan? In May a controversy-averse Walt Disney Co. ordered its subsidiary Miramax Films to dump the movie. But just weeks later Fahrenheit 9/11 copped the Palme d'Or (first place) at the Cannes Film Festival and eventually found other distributors, an indie coalition of the willing. By that time, the picture's incendiary charges and Moore's reputation as a folksy firebrand of the left had already begun to ignite accusations that he had twisted facts to suit his politics. Faster than you can say, "That's the kind of publicity no amount of money can buy," Fahrenheit 9/11 had become a secular Passion of the Christ and the most hotly debated political film since Oliver Stone's JFK 13 years ago.

But whereas JFK merely spun conspiracy theories about a dead President, Fahrenheit 9/11 goes after a sitting one with the explicit goals of unmasking his supposed crimes and removing him from office. Back when political bosses picked candidates and the rules of the game were arbitrated by newspaper editors and three network anchormen, for a mere movie even to attempt such a thing would have seemed folly. Today people get their news and, just as important, their attitudes from more rambunctious sources--the polarized polemicists on talk radio and cable news channels, comedians and webmasters. That's poli-tainment, and as practiced by Rush Limbaugh and other right-wing hosts on radio and by Matt Drudge on the Internet, it hounded Bill Clinton's presidency while spicing and coarsening the standards of political discourse.