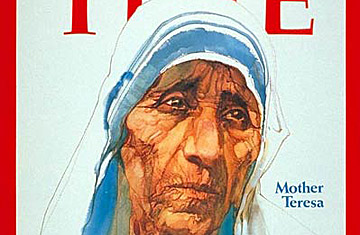

Mother Teresa

Calcutta presents a harrowing vision. The destitute, the skin-and-bones starving, the leprous and the dying seem to be concentrated there as nowhere else in India—or the world. Their numbers, swollen by past waves of refugees from Bangladesh, grow daily. At least 200,000 of them live in the streets, building tiny fires to cook their scraps of food, defecating at curbstones, curling up in their cotton rags against a wall to sleep—and often to die. Out of this scene of unremitting human desolation has come an extraordinary message of love and hope. Its bearer is a tiny gray-eyed Roman Catholic nun who 27 years ago, alone and virtually penniless, set out to work among the city's "poorest of the poor."

Today, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, 65, is slightly bent from hardship, her man-size hands are gnarled, her Albanian peasant face is seamed. From her solitary, seemingly foolhardy labors have grown two orders of women and men willing to take risks and make sacrifices. Nearly 1,300 Missionaries of Charity—1,132 nuns and 150 brothers—are now scattered throughout 67 countries tending the world's poor: in Yemen and Gaza, in Australia and Peru, in London and in New York City's South Bronx—even, at Pope Paul VI's request, in the shadow of St. Peter's.

Calcutta is still the heart of the effort. There, Mother Teresa and her followers collect the dying from the streets so that they may leave life in peace among friends. They rescue abandoned newborn babies from garbage heaps, nurse them back to health if they can, find homes for them later. They seek out the diseased and the hurt, sponging maggot-bloated wounds as if—an image that sustains them —they were sponging the wounds of Jesus. They have made havens for lepers, the retarded and the mad; they have found work for the jobless. "Not for a second did I think that God would act like this," Mother Teresa told TIME Correspondent James Shepherd in an interview last week. "We have nothing. The greatness of God is that he has used this nothing to do something."

Between her travels to the order's farflung outposts, Mother Teresa rises at 4:30 a.m., prays, sings the Mass with her sister nuns, joins them for a spare meal of an egg, bread, banana and tea, then goes out into the city to work. Age and authority have not changed her; she is at ease these days with Pope and Prime Minister, but she still cleans convent toilets. She has won an array of international honors, including India's Order of the Lotus and the Vatican's first Pope John XXIII Peace Prize, but sees them only as "recognition that the poor are our brothers and sisters, that there are people in the world who need love, who need care, who have to be wanted." Especially in a season that celebrates God's good will toward man, Mother Teresa's own loving luminosity prompts many to bestow on her a title that she would surely reject. She is, they say, a living saint.