(See Cover)

The jetliner left Atlanta and raced through the night toward Los Angeles. From his window seat, the black man gazed down at the shadowed outlines of the Appalachians, then leaned back against a white pillow. In the dimmed cabin light, his dark, impassive face seemed enlivened only by his big, shiny, compelling eyes. Suddenly, the plane shuddered in a pocket of severe turbulence. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. turned a wisp of a smile to his companion and said: "I guess that's Birmingham down below."

It was, and the reminder of Vulcan's city set King to talking quietly of the events of 1963. "In 1963," he said, "there arose a great Negro disappointment and disillusionment and discontent. It was the year of Birmingham, when the civil rights issue was impressed on the nation in a way that nothing else before had been able to do. It was the most decisive year in the Negro's fight for equality. Never before had there been such a coalition of conscience on this issue."

Symbol of Revolution. In 1963, the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, that coalition of conscience ineradicably changed the course of U.S. life. Nineteen million Negro citizens forced the nation to take stock of itself—in the Congress as in the corporation, in factory and field and pulpit and playground, in kitchen and classroom. The U.S. Negro, shedding the thousand fears that have encumbered his generations, made 1963 the year of his outcry for equality, of massive demonstrations, of sit-ins and speeches and street fighting, of soul searching in the suburbs and psalm singing in the jail cells.

And there was Birmingham with its bombs and snarling dogs; its shots in the night and death in the streets and in the churches; its lashing fire hoses that washed human beings along slippery avenues without washing away their dignity; its men and women pinned to the ground by officers of the law.

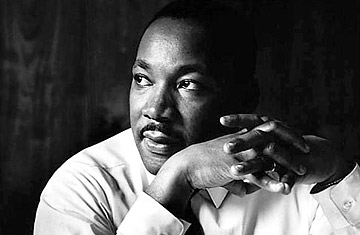

All this was the Negro revolution. Birmingham was its main battleground, and Martin Luther King Jr., the leader of the Negroes in Birmingham, became to millions, black and white, in South and North, the symbol of that revolution—and the Man of the Year.

King is in many ways the unlikely leader of an unlikely organization—the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a loose alliance of 100 or so church-oriented groups. King has neither the quiet brilliance nor the sharp administrative capabilities of the N.A.A.C.P.'s Roy Wilkins. He has none of the sophistication of the National Urban League's Whitney Young Jr., lacks Young's experience in dealing with high echelons of the U.S. business community. He has neither the inventiveness of CORE's James Farmer nor the raw militancy of SNICK's John Lewis nor the bristling wit of Author James Baldwin. He did not make his mark in the entertainment field, where talented Negroes have long been prominent, or in the sciences and professions where Negroes have, almost unnoticed, been coming into their own (see color pages). He earns no more money than some plumbers ($10,000 a year), and possesses little in the way of material things.

He presents an unimposing figure: he is 5 ft. 7 in., weighs a heavy-chested 173 Ibs., dresses with funereal conservatism (five of six suits are black, as are most of his neckties). He has very little sense of humor. He never heard