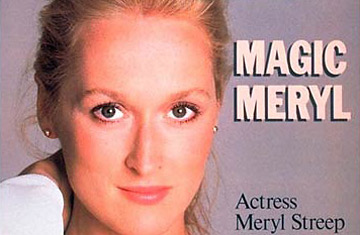

Actress Streep brings passion and skill to her richest role yet

The camera sees gray clouds, a churning gray sea, the spray-lashed stones of a harbor breakwater, and at the breakwater's end, facing seaward, the cloaked and motionless figure of a woman. A storm is blowing up. There is danger. A passerby, a tall, mustached young man, makes his way out along the breakwater to warn the solitary watcher. Over the rising wind he calls out to her that she is not safe. Now the mysterious figure turns, plucks aside the rough cloth of her hood and stares at the man, or through him, for a few moments. Then she turns again, having found no reason to speak, and once more looks out to sea. The young man, confused and troubled by what he has seen in her face, rejoins his fiancée, with whom he has been strolling, and retreats distractedly to the solidity of the shore.

This moody and romantic tableau, which is instantly recognizable as the opening scene of John Fowles' novel The French Lieutenant's Woman, is a cinematographer's delight. The breakwater exists, just as Fowles described it, at Lyme Regis, the small English sea-coast town of which he wrote. A film company needs only to go there, dress its actors in the costumes of 1867 (the story is a 19th century period piece, seen with irony through the filter of 20th century conceptions and misconceptions) and wait for dirty weather. All true, with only one complication: the look that Sarah Woodruff, the distraught figure on the breakwater, directs at Charles Smithson, the aristocratic young idler who approaches her there, must be so devastating that his comfortable life tumbles into chaos. He must, as the result of this unexpected collision with a woman of whom he knows nothing, begin a slide that leads him to jilt his wealthy fiancée, confess publicly to dishonor and lead the life of a lonely exile.

Clearly nothing as simple as mere beauty, or sensuality, or torment, or any ordinary combination of these qualities will reduce both Charles and cynical 20th century filmgoers to the requisite mush. Fowles uses a good many words and some carefully worked literary effects to evoke Sarah's strangeness: "It was an unforgettable face, and a tragic face. Its sorrow welled out of it as purely, naturally and unstoppably as water out of a woodland spring. There was no artifice there, no hypocrisy, no hysteria, no mask; and above all, no sign of madness. The madness was in the empty sea, the empty horizon, the lack of reason for such sorrow."

Does that do it? No, Fowles is not yet satisfied, and he goes back to work. "Again and again, afterwards, Charles thought of that look as a lance; and to think so is of course not merely to describe an object but the effect it has."