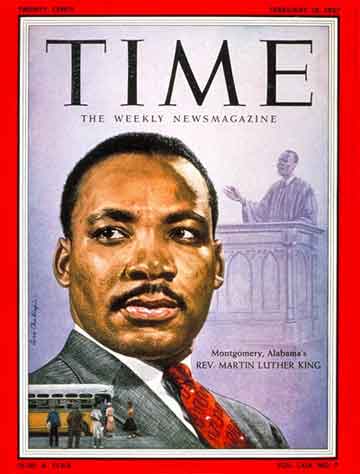

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

(9 of 10)

At 1 o'clock King goes home for lunch and an hour's rest. Then back to work. The phone rings and a secretary answers. Columbus, Ohio is calling: Could Dr. King address the local N.A.A.C.P. chapter? The secretary flips through an engagement book: "I'm awfully sorry, but Dr. King is so terribly booked up now. Could he make it some time later on?" A Negro comes in with a crudely printed hate sheet he has found on the street, hands it to a secretary, who smiles wanly: "Just another one. We get these all the time." The telephone rings again. This time the United Press is calling from New York, wanting to know if it is true that the Negroes have placed a guard on their leaders' homes and churches. "Why, yes," says King, "but it isn't new. We've been watching them for some time now." In an alcove next to a Coca-Cola machine, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy works at his desk, making final preparations for that night's mass meeting.

Onward, Christian Soldiers. The meeting is scheduled for 7 o'clock, but by 3 there are already 20 women waiting in the church auditorium (the meetings are moved each week from church to church to give each a sense of participation in the movement), and by 6 the hall is filled. As the starting time approaches, 40 Negro ministers file into their places near the altar. Finally, the electric clock on the balcony reaches 7 o'clock. King and his top assistants enter; the crowd rises and applauds wildly.

The singing starts, and like everything else, it is carefully planned. During the early days of the boycott, when the Negroes needed militant encouragement, there were such hymns as Onward, Christian Soldiers and Stand Up! Stand Up for Jesus. Today, love and forgiveness are stressed in hymns—Love Lifted Me, Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.

The Rev. Bob Graetz, the white minister, reads the 27th Psalm ("The Lord is my light and my salvation"). When Martin King arises for his "Official Remarks," he speaks quietly, making no play for the emotionalism that often marks Negro church meetings. ("If we as a people," he often tells his congregations, "had as much religion in our hearts as we have in our legs and feet, we could change the world.") Ralph Abernathy follows with what is frankly billed on the program as a "Pep Talk," and when Abernathy pep-talks, the hall is filled with the cheers and stomps of the crowd. The meeting ends; the Negroes slowly start from the church toward their homes.

Late at night, the mass meeting a warm memory, Martin Luther King Jr. can relax for a few moments before his prayers. He talks quietly of the broad principles on which his effort is based. "Our use of passive resistance in Montgomery," he says, "is not based on resistance to get rights for ourselves, but to achieve friendship with the men who are denying us our rights, and change them through friendship and a bond of Christian understanding before God." Impossible? Maybe.

But so, only 14 months before, was the notion that whites and Negroes might be riding peaceably together on integrated buses in Montgomery, Ala.