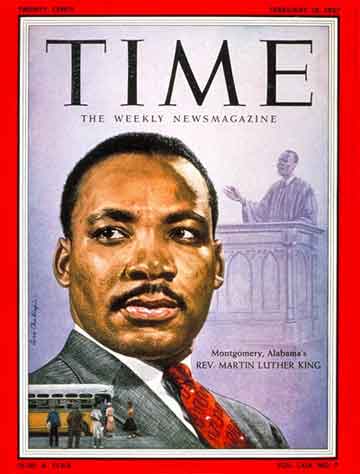

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

(8 of 10)

A Long Way to Go. At first, integrated buses on night runs were sporadically peppered with shotgun blasts. Then things seemed to quiet down. It was a false quiet. One night last month the stillness was shattered by a series of dynamite blasts. A bomb exploded outside the home of the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Negro pastor of the First Baptist Church, who has subordinated his own admitted ambitions for leadership to become King's strong, trusted right hand. Another bomb ripped into the home of a special object of white venom: the Rev. Robert Graetz, white pastor of the all-Negro Trinity-Lutheran Church, who has stood stoutly for integration. ("If I had a nickel for every time I've been called a nigger-loving s.o.b.," says Graetz, "I'd be independently wealthy.") Negro churches were also bombed (see map), and later an unexploded bomb was found on King's front porch. By now the great majority of Montgomery's law-abiding citizens realized that almost any solution was better than that offered by the terrorist minority. With every new outbreak of violence, inevitably followed by a reassuring word of nonviolence from King, white opinion grew stronger for accepting bus integration in an orderly way. The bus fight was to all practical effect, over.

"We have come a long, long way," says King, "but we still have a long, long way to go." The process will take time, since King is willing to move cautiously rather than excite new passions, especially over school integration. "If you truly love and respect an opponent," he says, "you respect his fears too."

Booked Up. King's post-boycott day begins when he arises at 6 a.m., dresses quickly in a grey suit ("I don't want to look like an undertaker, but I do believe in conservative dress"), takes an hour for reading, prayer and breakfast before going to the M.I.A. office, a small brick building on South Union Street. There two secretaries are already at work, pounding on their typewriters (the association receives and answers upwards of 100 letters a day), or cranking a Mimeograph machine to turn out official notices to the Negro population. King's desk is in a cramped, yellow-walled rear room, where he spends long hours conferring with M.I.A. committees, now expanded to include Registration and Voting (to educate Negroes and get out their vote as a political force in the community), Banking (to set up a credit union and consider a savings-and-loan association to provide capital for Negro housing and business) and Relief.