The raisins sitting in my sweaty palm are getting stickier by the minute. They don't look particularly appealing, but when instructed by my teacher, I take one in my fingers and examine it. I notice that the raisin's skin glistens. Looking closer, I see a small indentation where it once hung from the vine. Eventually, I place the raisin in my mouth and roll the wrinkly little shape over and over with my tongue, feeling its texture. After a while, I push it up against my teeth and slice it open. Then, finally, I chew--very slowly.

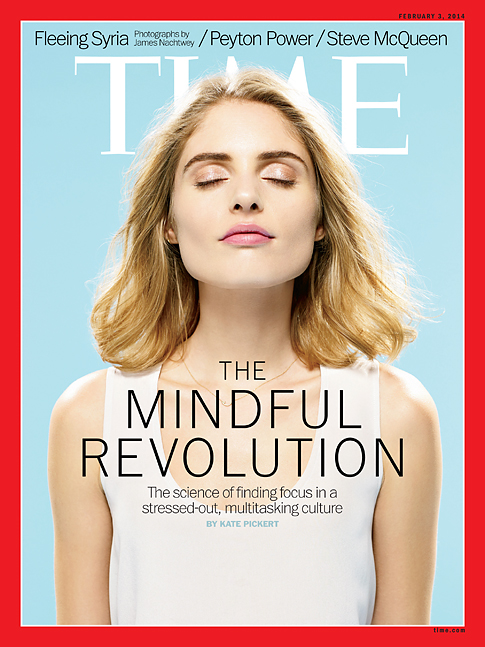

I'm eating a raisin. But for the first time in my life, I'm doing it differently. I'm doing it mindfully. This whole experience might seem silly, but we're in the midst of a popular obsession with mindfulness as the secret to health and happiness--and a growing body of evidence suggests it has clear benefits. The class I'm taking is part of a curriculum called Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) developed in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn, an MIT-educated scientist. There are nearly 1,000 certified MBSR instructors teaching mindfulness techniques (including meditation), and they are in nearly every state and more than 30 countries. The raisin exercise reminds us how hard it has become to think about just one thing at a time. Technology has made it easier than ever to fracture attention into smaller and smaller bits. We answer a colleague's questions from the stands at a child's soccer game; we pay the bills while watching TV; we order groceries while stuck in traffic. In a time when no one seems to have enough time, our devices allow us to be many places at once--but at the cost of being unable to fully inhabit the place where we actually want to be.

Mindfulness says we can do better. At one level, the techniques associated with the philosophy are intended to help practitioners quiet a busy mind, becoming more aware of the present moment and less caught up in what happened earlier or what's to come. Many cognitive therapists commend it to patients as a way to help cope with anxiety and depression. More broadly, it's seen as a means to deal with stress.

But to view mindfulness simply as the latest self-help fad underplays its potency and misses the point of why it is gaining acceptance with those who might otherwise dismiss mental training techniques closely tied to meditation--Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, FORTUNE 500 titans, Pentagon chiefs and more. If distraction is the pre-eminent condition of our age, then mindfulness, in the eyes of its enthusiasts, is the most logical response. Its strength lies in its universality. Though meditation is considered an essential means to achieving mindfulness, the ultimate goal is simply to give your attention fully to what you're doing. One can work mindfully, parent mindfully and learn mindfully. One can exercise and even eat mindfully. The banking giant Chase now advises customers on how to spend mindfully.