The ambition and aggression of the July 21 break into Iraq's biggest and most heavily fortified prison were trademarks of the man who planned it. It began with a barrage of mortars crashing into the open spaces inside the huge perimeter walls of what was once called Abu Ghraib and is now called the Baghdad Central Prison, on the outskirts of the Iraqi capital. Saddam Hussein had kept his enemies there once, and then the Americans had used it for theirs. Rebuilt and yet forever associated with the abuses that had happened there in the past, it is now the Iraqi government's main detention facility for extremists and terrorists, including hundreds of al-Qaeda militants. That's who the mastermind wanted out. He had wars to fight in two countries and a caliphate to establish across the historical lands of Islam, and he needed his fighters back.

The mortars sent the guards fleeing for their lives. Two cars, parked next to the perimeter and packed with explosives, then detonated, punching holes in the exterior walls. Some 50 men, armed with machine guns and grenades, rushed through the breaches. They raced through the corridors of the prison blocks, shooting out the locks of individual cells as they went. Within hours, 500 inmates, many of them high-value al-Qaeda operatives, battlefield tacticians and bombmakers — some arrested by U.S. troops before their 2011 withdrawal — were free. Shaky, green-lit video footage taken that night with a night-vision camera and later posted to jihadist websites shows the men whooping and calling out "Allahu akbar" — God is great — as they spill into the desert. Another video shows several hundred men piling into the backs of Toyota pickup trucks in a convoy destined for neighboring Syria.

The operation was barely noticed outside Iraq: the world was distracted by other horrors in Syria. But in jihadist circles, it greatly elevated the status of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the al-Qaeda leader who planned the breakout. Exactly one year before the Abu Ghraib attack, in an audiotape message to his followers, Baghdadi laid out plans for a yearlong campaign he dubbed "Breaking the Walls." It was only the second address he had delivered in his two-year tenure at the helm of al-Qaeda's Iraqi wing. Over the course of that 12-month period, he launched 24 complex car-bomb attacks and broke into eight other Iraqi prisons, liberating scores of al-Qaeda members. Abu Ghraib was his coup de grace. That one operation injected his organization with a vital influx of experienced, committed operatives — and their handiwork is writ large in the Middle East.

In Iraq, a brutal campaign of suicide attacks and car bombings has taken more than 3,000 lives in the past four months. In Syria's civil war, Baghdadi has become arguably the most feared and powerful man after President Bashar Assad. Counterterrorism analysts say the al-Qaeda inmates Baghdadi busted out of Abu Ghraib have become game changers: their arrival fortified the radical wing of the Syrian rebellion, and weakened the overall anti-Assad movement by frightening off international backers concerned about the growing jihadist influence. The rebels as a whole may be suffering under the sustained offensives of Assad's military, but Baghdadi's jihadists are growing in fighting capability and day-to-day influence on civilians' lives in a way that no al-Qaeda group has since Osama bin Laden's men enjoyed the freedom of pre-9/11 Afghanistan.

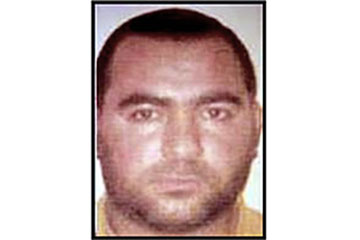

An enigmatic leader who shuns the spotlight — there is only one photograph of him in circulation, a grainy head shot the U.S. State Department uses to advertise the $10 million price tag it has put on his head — Baghdadi's ambitions match bin Laden's: to create a new caliphate, or state based on Islamic law, stretching across the Middle East and North Africa. Many jihadist leaders have stated this ambition, but Baghdadi is actually carving out a mini-caliphate in parts of both Iraq and Syria. Not even bin Laden, for all his spectacular international terrorist attacks, came close to holding so much as a square meter of territory in any Arab country.

To make his intentions clear, in April 2013, Baghdadi gave al-Qaeda in Iraq a new name: the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). With operations reaching from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, it is al-Qaeda's most successful affiliate. The war in Syria has made ISIS "the strongest of them all," says Jessica D. Lewis, director of research at the Institute for the Study of War in Washington and author of a recent report on al-Qaeda's resurgence in Iraq. "Baghdadi has military momentum, he has taken terrain in Syria, and he has established a governance system," she says. "He is the one conducting the war that all the foreign fighters are seeking. He is calling the shots, and that will make him a major player in al-Qaeda going forward."

Pretender to the Throne

The conflict in Syria has devolved into a three-front war. For the moment, al-Qaeda's affiliates are fighting on the side of the rebels, but their goal of establishing a broad Islamic empire anchored in Syria and governed by Baghdadi's interpretation of Islamic law puts them at odds with their supposed allies. Already Baghdadi has battled rebel groups he deemed insufficiently Islamic, forcibly taking towns controlled by moderates.