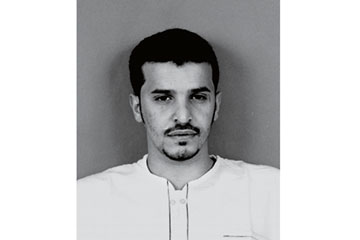

Saudi national Ibrahim al-Asiri has evolved into al-Qaeda's most inventive bombmaker.

Ibrahim al-Asiri didn't need Edward Snowden to tell him the U.S. might be tracking his telephone and Internet use. Last November, a drone-fired missile plunged out of the sky and killed al-Asiri's boss, the deputy leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), as he talked on his cell phone north of the Yemeni capital, Sana'a. "Lax security measures during his telephone contacts has enabled the enemy to [identify and] kill him," another AQAP member lamented on a video released July 17. Al-Asiri himself is in radio-silent hiding somewhere in Yemen, having been the target of repeated American drone strikes. The U.S. thought it killed him in a strike on Sept. 30, 2011, but he was not among the dead. In May 2012, another strike targeted a man emerging from his car: the CIA thought it was al-Asiri, but it turned out to be another AQAP leader.

There's a reason the U.S. has been hunting this Saudi Arabian national--little known outside counterterrorism circles--so hard. President Obama and his top counterterrorism officials believe al-Asiri is the most dangerous terrorist in the world. His fingerprints were found on the "underwear bomb" that failed to blow up when a young Nigerian suicide bomber tried to ignite it aboard a U.S.-bound airliner on Christmas Day 2009. Al-Asiri also built the bombs hidden in printer cartridges that came within hours of blowing up two Chicago-bound international cargo planes in October 2010: a tip-off by a Saudi Arabian intelligence mole within AQAP led to the bombs' being found and removed. In May 2012, al-Asiri's plan to blow up a U.S. airliner around the anniversary of Osama bin Laden's death was foiled when an AQAP member who volunteered for the suicide mission turned out to be a double agent and handed the master bombmaker's latest, improved version of an underwear explosive over to the FBI.

Al-Asiri's bomb designs are growing ever more ingenious the longer he remains at large. Speaking at the Aspen Security Forum in Colorado in mid-July, Transportation Security Administration (TSA) chief John Pistole said the 2012 version of the underwear bomb showed three dangerous innovations that made it more reliable and harder to detect than its predecessors. First, al-Asiri had used a new type of explosive "that we had never seen," Pistole said, and that no machine or dog had been calibrated or trained to detect. Second, the bomb had a "double initiation system" using two syringes of chemical detonators, instead of one, like the Christmas Day bomb that failed. Finally, al-Asiri encased the bomb in common caulk to limit the explosive vapors that scanners might detect, Pistole said. "We're dealing with a determined enemy who is innovative in his design, construction, concealment and deployment of improvised explosive devices," Pistole said.