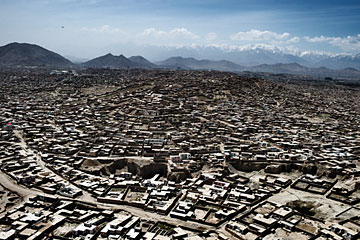

An aerial view of Kabul. The threat of a serious economic reversal is becoming a daily concern

(3 of 3)

The Long Game

Prospects are even worse outside Kabul. De Naw is only about 30 km from the capital; the sprawling hulk of Bagram Air Base can be seen from the road that leads into the village. On a warm Friday afternoon in May, little girls in their best frilly dresses and glitter eye shadow hang around De Naw's main drag, while their parents eat in separate rooms at a wedding feast. Before long, figs and cherries will be falling off the trees, but those aren't enough to feed the hundreds of families who live there. For years, men have been leaving their homes and crossing illegally into Iran to find work. "A lot of our friends and family have already left, come back and then gone back again," says Aslam, who was 15 when he first went to Iran. He was deported after a few years. Now, at 22, he is unemployed, like most men in De Naw. "It's the same situation all over Afghanistan," says Aslam, who like many Afghans only uses one name. "Nobody has a job."

Next year, the combat troops will leave, and life in De Naw will go on as it has been for years. The same will be true in many other parts of the country — because the real economic impact that tens of billions of aid and military dollars have had in Afghanistan is depressingly small. More than a third of the country still lives beneath the poverty line. Life expectancy — 50 years in 2013 — has improved only marginally in the past decade. About three-quarters of the population can't read or write.

A 2009 study conducted by the nonprofit foundation Peace Dividend Trust (since renamed Building Markets) concluded that, excluding security and military spending, less than 40 of every development-aid dollar spent in Afghanistan reached the local economy through, for instance, salaries. But the loss of even that contribution will be sorely felt in Kabul and more so in violence-prone areas that have had a larger military presence and thus been the recipients of more resources. The challenge for the Afghan government will be to figure out how to make enough money — and distribute it transparently — so that villages like De Naw do not get left behind and descend into violence.

Where will that money come from? The development of Afghanistan's mineral, oil and gas resources is being pushed aggressively by the U.S., which is still by far Afghanistan's largest single-country donor: USAID funding will total about $1.6 billion in 2013. (The Asian Development Bank, by comparison, is slated to donate $527.4 million this year.) Mineral, oil and gas extraction have the potential to generate much needed revenue and, to a lesser extent, jobs. But few expect to see any significant returns from mining for decades, and the extraction and transport of any natural resource will need substantially more outside investment for it to get started in earnest. Focusing more money on improving agriculture, which already contributes either a third or a quarter of annual GDP, depending on the harvest, could have a more immediate impact. But as public support dwindles in the West for sending aid to Afghanistan, the government will have to lead the charge in developing both sectors. "We need to show progress to justify the resources we are providing," says Yamashita of USAID, whose budget is already dropping from $3.5 billion during the 2010 surge to $1.6 billion this year. "We have to show there is political will."

In the end, it is the Afghans who remain — more than the politicians, or the soldiers, or the international donors — who will define what lies beyond 2014. Many are leaving, but many more, of course, can't. Or won't. Fawad Saffi slumps on a large sofa in the Milli Factory compound, toggling through YouTube videos of the factory during its heyday. Since his father was kidnapped and held for ransom, the Saffis have been working and living behind the tall walls and barbed wire of the factory grounds. Saffi, who was shot in the stomach during a kidnapping attempt when he was 18, doesn't travel without armed guards. It's hardly a normal life for a well-to-do 21-year-old, and his friends from Kabul's international school who have moved to the U.S. or to Europe think he's crazy for not joining them. "Their goal is to have fun," Saffi says. "My goal is to stay and help the country." He pulls up another old video of the factory in full swing, with women hunched over their sewing machines and men gluing soles on thousands of pairs of clean, tan boots. "This is my place," he insists. When the deal is no longer a deal, only hope remains.