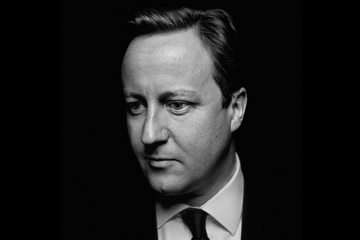

Shoes discarded, David Cameron pads down the aisle of a private charter jet with a chocolate-frosted cake. It is May 15, and he is returning from a four-night, three-city visit to the U.S. In London, more than a third of Conservative MPs have just refused to back his legislative program because it doesn't enshrine in law his promise of a referendum on Britain's membership in the European Union. Britain's Prime Minister seems blithely unconcerned. His communications chief and a protection officer are celebrating their joint birthdays, and Cameron dispenses torte to the traveling press.

A headline writer for a British tabloid might pounce on this as Cameron's Marie Antoinette moment: LET THEM EAT CAKE! A full-blown insurrection is brewing in the Tory party, and many in the media say the aristocratic politician is out of touch, too posh to properly connect with voters or his own backbenchers. A significant proportion of Britons believe the nation is under attack from trendy liberal values and from European bureaucrats. Traditionally Tory supporters, they do not trust the sophisticated, metropolitan Cameron who wears his conservative convictions lightly. Over the past year, increasing numbers of them have switched allegiance to the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), an upstart band of Euroskeptics.

This is not merely a domestic political issue for Cameron and his Tory party. In seeking to unify his party and undercut UKIP's appeal, the Prime Minister has started a process that could redraw not only Britain's relationship with Europe but the European Union itself. In a Jan. 23 speech in London, he pledged a referendum before the end of 2017 allowing Britons to decide whether to remain part of the E.U. or leave it. His view is that Britain should stay, on renegotiated terms. But a plurality of his compatriots disagree, favoring a British exit by 43% to 37% according to a May 15 poll.

The political turbulence in Britain has left continental European leaders irritated and anxious in equal measure. "Europe existed before Britain joined it," sniffed French President François Hollande at a May 16 press conference in Paris. In truth, Europe would look very different shorn of its most outward-facing nation--a useful counterweight to the impulse to state intervention and protectionism that is much stronger in other E.U. countries, especially Hollande's.

Cameron arrived in Washington, the first stop of his U.S. tour, to discuss June's G-8 summit, which he is hosting in Northern Ireland. He also pushed for a free-trade deal between the U.S. and the E.U. as an important plank in building a sustainable global recovery. But a large elephant loitered conspicuously in the East Room of the White House as Cameron and President Barack Obama held a joint press conference on May 13. If the referendum goes as UKIP and many Tory backbenchers would like it to, Britain may not be part of that free-trade deal.