(8 of 8)

But if you need the ultimate proof that millennials could be a great force for positive change, know this: Tom Brokaw, champion of the Greatest Generation, loves millennials. He calls them the Wary Generation, and he thinks their cautiousness in life decisions is a smart response to their world. "Their great mantra has been: Challenge convention. Find new and better ways of doing things. And so that ethos transcends the wonky people who are inventing new apps and embraces the whole economy," he says. The generation that experienced Monica Lewinsky's dress, 9/11, the longest wars in U.S. history, the Great Recession and an Arab Spring that looks at best like a late winter is nevertheless optimistic about its own personal chances of success. Sure, that might be delusional, but it's got to lead to better results than wearing flannel, complaining and making indie movies about it.

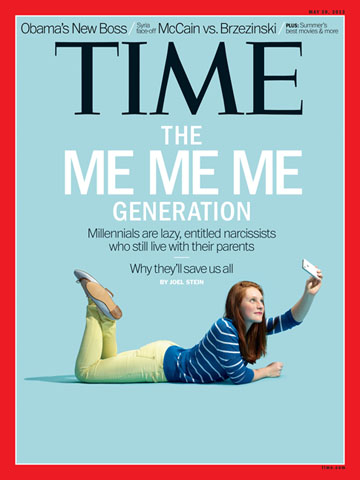

So here's a more rounded picture of millennials than the one I started with. All of which I also have data for. They're earnest and optimistic. They embrace the system. They are pragmatic idealists, tinkerers more than dreamers, life hackers. Their world is so flat that they have no leaders, which is why revolutions from Occupy Wall Street to Tahrir Square have even less chance than previous rebellions. They want constant approval--they post photos from the dressing room as they try on clothes. They have massive fear of missing out and have an acronym for everything (including FOMO). They're celebrity obsessed but don't respectfully idolize celebrities from a distance. (Thus Us magazine's "They're just like us!" which consists of paparazzi shots of famous people doing everyday things.) They're not into going to church, even though they believe in God, because they don't identify with big institutions; one-third of adults under 30, the highest percentage ever, are religiously unaffiliated. They want new experiences, which are more important to them than material goods. They are cool and reserved and not all that passionate. They are informed but inactive: they hate Joseph Kony but aren't going to do anything about Joseph Kony. They are probusiness. They're financially responsible; although student loans have hit record highs, they have less household and credit-card debt than any previous generation on record--which, admittedly, isn't that hard when you're living at home and using your parents' credit card. They love their phones but hate talking on them.

They are not only the biggest generation we've ever known but maybe the last large birth grouping that will be easy to generalize about. There are already microgenerations within the millennial group, launching as often as new iPhones, depending on whether you learned to type before Facebook, Twitter, iPads or Snapchat. Those rising microgenerations are all horrifying the ones right above them, who are their siblings. And the group after millennials is likely to be even more empowered. They're already so comfortable in front of the camera that the average American 1-year-old has more images of himself than a 17th century French king.

So, yes, we have all that data about narcissism and laziness and entitlement. But a generation's greatness isn't determined by data; it's determined by how they react to the challenges that befall them. And, just as important, by how we react to them. Whether you think millennials are the new greatest generation of optimistic entrepreneurs or a group of 80 million people about to implode in a dwarf star of tears when their expectations are unmet depends largely on how you view change. Me, I choose to believe in the children. God knows they do.

The original version of this article said that Jean Twenge is a professor at the University of San Diego. Twenge is a professor at San Diego State University.